It happens to every angler who fishes moving water. You step to the edge of the river, get a lay of the land, pick your spot, and start fishing. Meanwhile, another angler steps in above or below you, throws in a cast, and immediately hooks up. You carry on fishing as the angler plays his fish, releases it, and then goes back to fishing. Soon enough, that angler has another fish on. And so it goes. Did this angler have a more refined presentation? Better lure or bait? Or was it something else?

As someone who has been on both sides of that equation, I suggest another possibility: The angler walked the river, looked at the conditions, and read the water that the fish would be holding in. It’s a skill not every angler is born with, but it is a skill that can be developed.

Sure, you can have the best gear, finest waders, and be able to cast a full fly line out with one hand and potentially catch a fish. But day in and day out, if you can’t properly read the water of a river or stream, you are going to be at a distinct disadvantage. The ability to see how water is moving and where fish might hold in that water is a skill that will serve every angler well. Trout, salmon, and other species use current — or lack thereof — in different ways. Here are a few of my thoughts about what to look for in a variety of river conditions.

High water frustration

Nothing is more frustrating to most river anglers than high water. Even when the water is clear, high flows will always present a challenge. The traditional pools and runs that anglers gravitate to under normal conditions may not be fishable, or will be extra challenging. Keep in mind that in rivers fish generally hold in places with the least water resistance.

In high water, current is slowest at the bottom, directly in front of or behind barriers (such as boulders, trees, or wing-dams) or tight to the shore. I learned this lesson many years ago on a river called the Wolf, east of Thunder Bay. The spring thaw had put the river way up high, and it was like chocolate milk. Yet the steelhead run had been on for a few days and they had to be hiding somewhere.

The search started via float and roe bag in the centre of the river, but the mad current just swept everything away. As I was adding more shot to the leader, I noticed a swirl on the far bank, just a few feet from shore. The water was usually shallow there, but there was clearly enough flow to be holding a fish. I shortened up my leader, and threw the whole rig right across. The float drifted a short ways and then buried. I lifted the long rod and felt the pulse of a rainbow.

After that fish was released, I looked at the water at my feet with new eyes. Could it be? There was a bit of a ledge, and certainly enough water for a trout. The float was pitched up the shore and I followed it down the shore with my rod tip. Once again the float buried and a trout was on. These high-water steelhead were hugging the bank. It was a lesson I’ve never forgotten. The water along shore has the least resistance and provides a perfect hold for fish.

Pools, runs, riffles, and tailouts

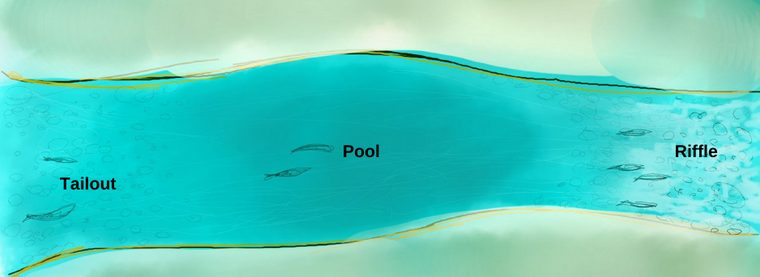

It’s nearly impossible to describe or explain how a typical pool works, as they are all so different. The key typical elements are the riffle, generally located at the head of the pool, the main belly of the pool, which has the deepest water, and the tailout, where water spills into rapids.

The tailout is the break where water leaves the pool and features a calm and predictable current for fish. This calmer water allows migrating salmon and trout to rest, but also provides a fantastic place to feed, as food washes down to them. Tailouts tend to be shallower than the main pool, so it’s less of a trip to the surface for a trout to take a fly. For some reason, many fish seem to be more apt to hit sitting in a tailout as well.

The main belly of the pool, which can also be called a run if it is on the swifter side, is a natural parking place for migrating fish. The deeper water provides safety and the flow at the bottom is gentler than the surface water. It can become a place for resident fish to live in the heat of summer and in the winter as well. Slower presentations may be required here, although occasionally a spoon, spinner, or large streamer will do wonders.

The head of the pool, or riffle, can be a hotbed of fish activity, and is often the fly angler’s favourite domain. Trout and salmon move into riffles to feed on insects and dislodged eggs. The riffle is often where the well-aerated gravel needed for spawning is found. Water here is generally shallower and turbulent. That turbulence allows even large fish to move into it without being detected. Morning and evening are key times for fish to use riffles.

Falls worth a try

Falls are often barriers to fish migration, or at the very least slow them down. This means the plunge pool below a fall is always worth a try. Fish holding directly below a falls are less likely to hit as they are focused on migration. Fish that are holding at the tailout, however, or in pockets of slower water below the falls, are more liable to bite. A large boulder below a falls will provide a break that fish will sit behind. One other thing. The tops of falls, before they break over the fault, can be a great place to catch fish as well. Fault lines are often associated with springs, and brook trout, in particular, love springs. Never overlook the top of a fall when chasing fontinalis.

That’s a basic guide to reading water. The “book” always changes, however, so the more time spent reading the better. It’s not the worst type of homework you can have.

Senior Editor Gord Ellis is a journalist, radio broadcaster, photographer, and professional angler based in Thunder Bay. Reach Gord at: [email protected], Twitter: @GordEllis

Originally published in the April 2020 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS magazine.

Leave A Comment