The number of wild turkeys in Ontario continues to increase, bringing with it a new question. Are there diseases that could spread and deplete turkey numbers? Fortunately, turkeys are so far proving to be a hardy species.

A 2016 study by Amanda MacDonald at Guelph University looked at the cause of death in 56 wild turkey carcasses submitted to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperation between 1992 and 2014.

The study was done to gain a better understanding of the current health status of the wild turkey.

Some diseases found can be watched for in the turkey woods. There are signs to look for which might help increase our knowledge of the effect of these diseases on Ontario’s wild turkeys.

Viral diseases

Avian pox

Avian pox is a viral infection transmitted by mosquitos and direct contact with an infected subject.

Symptoms include obvious lesions on  featherless parts of the body that can also occur in the mouth and throat. These lesions can affect breathing and eating. Lesions can also cover the eyes, impacting sight.

featherless parts of the body that can also occur in the mouth and throat. These lesions can affect breathing and eating. Lesions can also cover the eyes, impacting sight.

Harvesting an infected bird is possible. But due to the large lesions, it’s likely the infection would be spotted before harvesting the bird.

Avian pox is not known to infect humans, but the sight of the bird may be enough to deter anyone from wanting to eat the meat.

Avian pox is still a relatively new disease, though reported cases are increasing. This may point to it as an emerging viral disease.

Lymphoproliferative disease virus (LPDV)

LPDV is another newer viral infection impacting wild turkeys. Symptoms include lesions on the head and feet, and possible tumours on the spleen and liver. However, turkeys can have LPDV without showing any symptoms. It’s possible to have harvested a turkey with LPDV and not know it.

How the disease is transmitted in wild and domestic turkeys is still unknown. The wide geographic distribution and high prevalence of LPDV in poultry may seem like threats, but there are still knowledge gaps. This makes it hard to assess what risks the disease poses to the wild turkey population.

Parasitic disease:

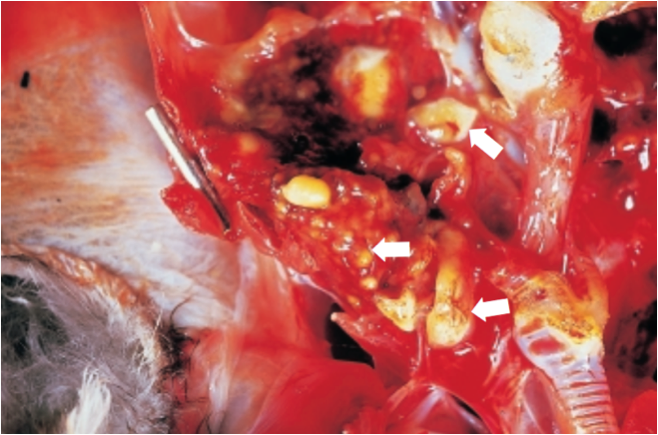

Blackhead disease

Blackhead is a parasitic disease. The parasite is carried by the common poultry cecal worm and is transmitted when birds ingest the eggs of the worm.

The parasite does not affect humans.

Symptoms in turkeys include lethargy, loss of appetite, ruffled feathers, and often sulfur yellow-coloured feces. A blue/black colouration of the head sometimes, though not commonly, develops. The liver will also contain pale grey or yellow circles that are characteristic of blackhead.

It’s possible to harvest a turkey with blackhead that doesn’t exhibit any other signs.

Bacterial disease

Avian cholera

Avian cholera is a contagious disease. It results from an infection by the bacteria Pasteurella multocida.

The bacteria is transmitted between birds through mucus membranes in the throat or upper air passages or through cuts and abrasions.

Infections are common in waterfowl and often result in death 24 to 48 hours after exposure.

Major outbreaks in species other than waterfowl are rare, making cases of avian cholera uncommon in wild turkeys.

Obvious signs in the field are often behavioural. Birds appear lethargic, fly erratically, and have mucous discharge from the mouth. There can also be lesions in the heart and liver.

There is not a high risk for transmission of the disease to humans, but it is not recommended to eat meat from an infected bird.

Fungal disease

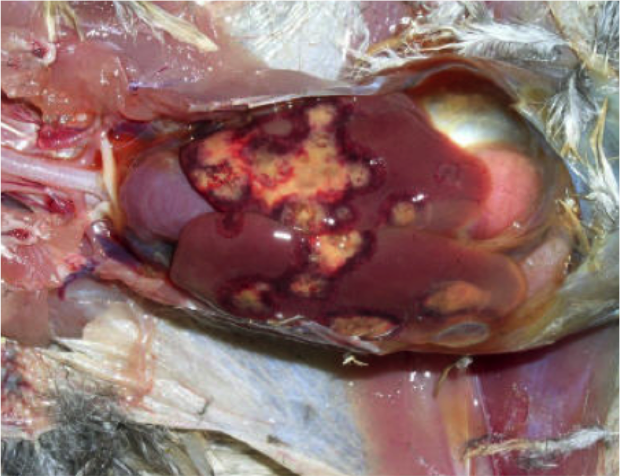

Aspergillosis

Aspergillosis is a fungal disease of the respiratory tract and is found worldwide in almost all mammals and birds. The fungus is transmitted through spores and can’t be passed directly from  bird to bird.

bird to bird.

Birds usually become infected by inhaling airborne spores while feeding near contaminated sources.

The spores become lodged in the air sacs, resulting in the thickening of the their walls. This causes pneumonia or osteoarthritis to develop.

Symptoms usually include loss of appetite, respiration abnormalities, and diarrhea. There can also be yellow lesions that look similar to cheese throughout their lungs and air sacs.

It’s not possible for humans to contract the fungus from eating the meat of infected birds, but inhaling the spores is possible and could lead to transmission. Consuming an infected bird is not recommended.

Is there a vaccine for avain pox?

What could be the possible medicine for treating wounds mostly on turkey’s head?

Thanks best regards.

Thanks for the note, Kirya. No vaccine for humans. Not sure if we’re in a position to answer your second query. Cheers.