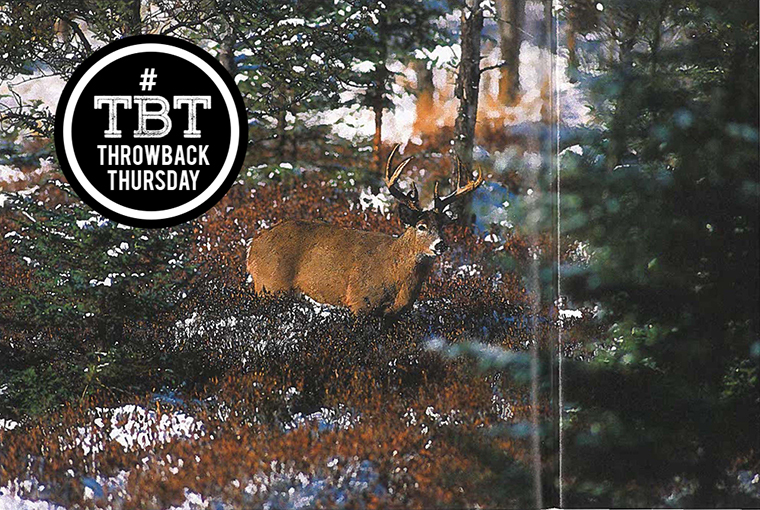

Deer were moving. A light skiff of fleecy snow on a crunchy base revealed fresh tracks made by two or more whitetails. As I made my way slowly along a rocky, open spruce and pine ridge and through a shallow cut-over hollow, I was careful not to break branches or step on a windfall and alert deer deer to my presence.

Some noises, like the crunch of the snow under my feet, didn’t concern me. As long as I varied my pace and gait, to emulate the actions of a deer or a moose, and spent as much time stopped and peering into the woods as I spent on the move, I felt comfortable. It took me about 45 minutes to make my way from the truck to the edge of timber along a wet alder and sedge swale, a distance of less than a third of a mile (half a km).

Stopping again to look and listen, I felt a cold breeze wash my face. “Good,” I thought, I’m still working into the wind, but a thud of hooves and the flash of white tails ended my complacency. Had the deer seen me or had they heard me? Haw badly had they been startled? Keeping my position, I could hear the loud crunching of frozen leaves as the deer ran a short distance and stopped. A couple of loud blows followed, and then the deer — two of them, I figured — walked slowly and quietly out of hearing range. The cold, now much more bearable, still bit at my nose and ears as I waited and reformulated my plan.

Why stalking?

In Ontario’s woodlands, sudden and unexpected encounters with deer of the close kind are the rule, not the exception. When stalking deer, an indisputable fact is that most of them will see you long before you see them. Walking around in the woods and looking for a deer to shoot is tough work. It’s why the majority of deer hunters use stands or make drives. When queried about tactics, though, most versatile hunters agree that, despite the difficulties and demands required to stalk deer, no other hunting style is as exciting. Finally, as a bonus, stalking hunters take some of the biggest bucks.

Success, though, requires a recipe of ingredients. While styles and methods used vary, there’s strong commonality with the basics. Perhaps most important is that stalkers need to be in good shape. Reasonable strength, endurance, and general good health are desirable qualities. Stalking often involves traversing rough terrain for hours, climbing up and down slippery slopes or wading through deep snow. If you’re overweight, have a heart condition, or have a bad back or arthritic knees, stalking is not for you.

You also need to feel at home in the woods, not be in constant fear of becoming lost. Stalking deer often takes you far from roads and familiar terrain. Being comfortable with a map and a compass, or competent with a GPS unit, are trademarks of almost every good deer stalker. So is access to a lot of land. There’s little sense in trying to stalk deer in a 40-acre (16 ha) wood lot.

Stalking in comfort

Choose clothing and equipment carefully. Your feet need light, insulated, waterproof boots, with good grips on soles and firm ankle support. I prefer rubber boots with removable felt liners. To accommodate warm or cold temperatures, I have two pairs to choose from. Clothing needs also vary with temperature and other conditions, but the rule of thumb is to go as light as possible. Layer to keep warm. Peel to cool down.

The best of clothes are of little use if they can’t muffle sounds of walking through twiggy nightmares. Fleece and similar soft-napped fabrics, common on many hunting jackets, vests, and outer shells, are the best choices, as long as the ensemble breathes, is matched to the temperature regime, and allows freedom of movement. The same goes for pants or coveralls. My choice of fabric for pants, though, is wool woven with 20 to 40 per cent polyester for durability. Insulated shooting gloves are also a must.

A day pack is another essential. It should also be covered with sound-silencing material and be comfortable to wear. Backpacks are best for those who like to tote a lot of gear, including first-aid kits, a Thermos, knives, saws, sharpeners, rope, extra clothing, and Dagwood-size sandwiches. With the exception of a Thermos and a change of clothes, though, enough gear to satisfy food and safety requirements can be stashed into a fanny-pack. Keep your pack as light as possible.

Most pack hunters assume stalking is only for those who prefer to lug a gun, but there’s no reason why bow hunters can’t participate. Aboriginal deer hunters historically never had access to portable deer stands.

Stalking vs tracking

Stalking is often confused with tracking. While there are similarities, there are also important differences.

Tracking is to chase and follow a specific animal by using tracks, spoor, and other signs. Stalking is more the art of ambush. It can be practised whether or not the exact whereabouts of animals is known. One often hears the term “stalking of the woods” when describing a deer stalker’s typical hunt. following a blood trail would be properly called tracking, although stalking techniques might be necessary, especially if the deer is wounded.

Deer stalking also has considerable affinity to slip hunting. This describes how hunters move stealthily through the forest, from one ground stand to another. As such, it is seldom used to describe a stand-alone hunting method. In this context, though, it’s usually referred to as “stand-and-slip hunting.” While stalking employs basic techniques of this, other key hunting elements are also included. To be engaged in stalking, the stand-and-slip hunter is trying to get into a position for a shot on an animal already seen or one being tracked.

Hunters who stalk might also be simply working forest stands, adjusting personal movement patterns to suit the stand’s characteristics. Most hunters, of course, do things differently on an open oak ridge top than down in a cedar glen. Learning how to move around in the forest, managing to see deer and create shooting opportunities is what the good woodland deer stalker does.

Good things take time

To successfully stalk deer takes weeks or even years of practice. It’s important not to get discouraged with an initial lack of success. Money won’t let you buy technology that will instantly turn you into a great deer stalker. There’s no substitute for practice, patience, and perseverance. There are, however, basic elements that must be a part of every deer stalker’s repertoire.

Always try and work into the wind. When planning a day’s hunt, have alternative directions to head. If necessary, keep adjusting plans on where to go and what to do in response to wind shifts, time of day, and other factors.

Be as quiet as possible and try to keep your outline broken. Test your footing before applying weight. Avoid walking on logs and breaking branches with your hands. Don’t walk the crest of a ridge or the centre of a forest opening unless absolutely necessary. Keep away from dense thickets, though. Except for train networks, which are generally hard for the upright form of a a human hunter to use, deer use dense woods much less than most hunters think they do. Active deer prefer areas that, while they might seem thick, are still open.

Deer woods are a joy

Good deer woods are often a joy to be in. Even if deer are in dense stuff, trying to go in after them is pointless. They’ll always know exactly where you are, shooting conditions are terrible, and more than likely you’ll rip your clothing and skin to shreds.

Constantly look and listen. It’s possible to see deer before they see you, although the odds are usually with the deer. Even though they might spot you first, they won’t necessarily run off. How well deer blend into the forest and hide is remarkable. In most instances, how a hunter behaves once a deer has been spotted determines whether the animal will take flight or remain still and allow time for a shot. By not acting startled and not abruptly changing your actions, deer might remain quiet. Avoid direct eye contact, though.

Deer can often be heard moving at quite a distance. With practice, deciphering whether deer are walking, running, or chasing around is not difficult. Occasionally, hunters hear bucks thrashing bushes with their antlers, and on rare occasions a fight is heard. A few years back, I shot a nine-point buck after having heard antlers slap dead, brittle lower branches in a patch of balsam on a hillside ahead of me. When the deer moved again, I was able to spot and shoot it at a distance of just under 110 yards (100 m). I’ve heard bucks grunting on several occasions during the last couple of years. Last fall, hearing a buck grunt twice, I was able to slip behind a clump of young mountain maple and spot a six-pointer shuffling beneath the canopy of a small stand of large spruce and balsam.

Tools to use

While stalking, I frequently use a variety of deer calls to attract whitetails and to help disguise my presence. On a hunt last year, I made a single, distinct grunt to try attracting a deer I heard jump when my partner, stalking with me nearby, startled it from its bed. I can’t be certain the deer responded to the grunt, but the 13-pointer trotted right to be.

Although stalking is an ancient art, modern technology can be of assistance. Stalkers commonly use GPS units to record and relocate remote areas deer frequent. Many hunters use binoculars or spotting scopes to see distant deer. For them, the glassing of a hillside or a valley, spotting a deer, deciding the animal is worth trying for, and then planning and executing a successful stalk is a classic hunt. But it need not be a successful classic glass-and-stalk to be remembered.

Buck in the area

After I waited for the woods to quiet and the deer I’d jumped to mosey off, I made my way slowly down a short, steep slope and found tracks in the snow beneath jack pines. The tracks looked small, and there was no tell-tale drag of a buck. ”Does,” I thought. But I wasn’t looking for a doe. I’d hunted the area a week previous and had seen huge rubs on several large spruce and poplars. I knew there was a buck in the area.

I crossed a deserted winter logging road and took an old skidder trail up the hill. The trail, largely grown in with alder, willow, and the occasional conifer, had been used regularly by deer. Halfway up the hill there was a large, fresh scrape under a spruce. In the freshly turned earth, I could clearly see the large hoof print of a buck.

Quickly, I followed the trail to a plantation of perhaps 100 black spruce about three feet (1 m) in height. In the middle of them, a small pine that loggers had left behind had been vigorously rubbed by a buck. The rub, despite being the colour of the early season snow, stood out in the spruce’s green foliage. I still hadn’t heard or seen the buck, but my senses were peaking with anticipation. I picked my way through the plantation and found myself at the edge of a rocky ridge looking down a slight ravine leading to a huge cat’s-tail marsh.

The logging road I’d crossed earlier had swung around the base of the hill, and I could see it down and to my right. Keeping my silhouette back from the lip of the hill, I stopped beside a small bunch of balsams to look and listen. With my heart pounding and my ears ringing, it took several motionless moments before I heard the unmistakable sounds of hooves crunching granular snow. Straining, I tried to key in on the deer, but saw nothing.

Spying movement

Finally, behind a string of thick spruce and balsam on the far side of the logging road below, I spied movement. A deer was quartering towards me. I saw antlers and knew this was the deer I was after. The buck, head down and moving with a purpose, gave no indication it knew of my presence. But the trees that concealed me were now obstructions.

I needed to get to a rocky outcrop about 16 yards (15 m) to my right, if I was to have any chance for a shot. I had to take my eyes off the deer to keep my balance on the hill, stay quiet, skirt around a couple of trees and bushes, and get to the rock. It took every ounce of concentration I had.

Just as I was slipping into position, I saw the buck again. Still on a mission, it stepped through a small opening and gave me another glimpse of antlers and chest. A second opening just ahead gave me a chance to shoulder the little.243 and hope the deer wouldn’t veer away. It didn’t. The fine buck had a great rack, with six points on the left beam and four on the right.

Stalking, like any other hunting technique, won’t guarantee success. It’s tough and demands finely honed skills. For thrills, excitement, and a sense of satisfaction, though, no other hunting style can compare.

Originally published in the September 1998 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS magazine.

Bruce Ranta is a retired wildlife biologist, outdoor writer, and photographer based in Kenora. Reach Bruce at [email protected]

Leave A Comment