Every fall, usually at about the time of the first snowfall, a condition known as “ice fever” emerges in Ontario’s ice anglers. First ice provides great action, but the urge to get out must be tempered with a fundamental awareness of ice safety. We must also understand how changing environmental conditions modify the structure of lake ice, almost daily. The physical forces, which shape the seasonal life of ice, can be predicted and utilized to ice anglers’ advantage.

Birth of surface ice

In late fall, the warmer upper layer of water cools and mixes with the colder bottom layer. This event is called turnover. At 39 ̊F (4 ̊C), the maximum density of liquid water, new layers form. Warmer, denser water on the bottom and colder, lighter water on top. At 32 ̊F (O ̊C), with minimal wind or current, surface water turns into ice crystals along the shoreline. Ice forms slowly from shore towards deeper water. Wind will cause ice to break temporarily. Air temperature will dictate the rate of re-freeze. Any snow cover (insulation) will slow the ice-making process.

Ice types

White ice: Forms on the surface from a mixture of melted snow, rain, and lake water upwelling from cracks. It appears white, containing air, cracks, and suspended solids. Poor ice strength.

Black ice: Is twice as strong as white ice. It is clear and contains few imperfections. It freezes from the bottom up. Four inches of black ice topped by eight inches of white ice equals 4 + (8/2) = 4+4 or eight inches of equivalent strength.

Cracks, slush, and wind

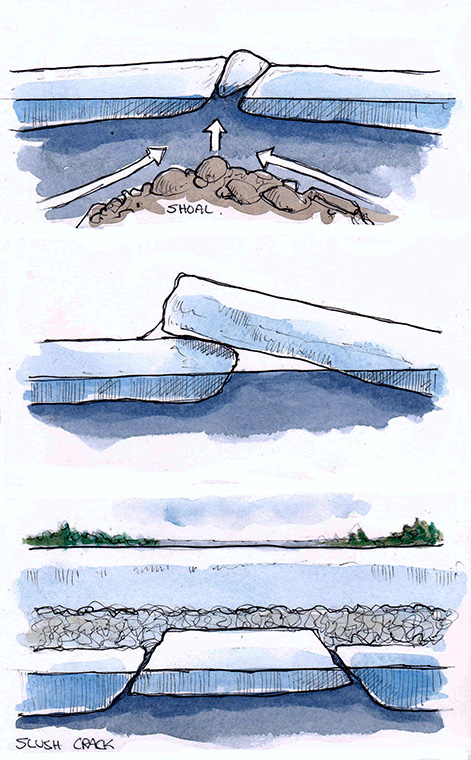

When snow accumulates on the ice, it creates weight, which pushes down on ice. Where there are cracks, water from underneath is forced to the surface where it mixes with snow, forming slush. Slush will not usually freeze, since snow on top acts as an insulator. When slush eventually freezes, it forms white ice.

Cracks and ridges are formed as ice contracts and expands due to temperature changes. They usually originate from ice stress at point-to-point on a lake or along shorelines. They are extremely dangerous to cross.

Folded ridges develop slower than overlapped ridges. Water covers the surface of the hidden ridge and may freeze, creating a thin layer of ice hiding open water underneath.

They are active and are continually opening and closing.

Winds of 50 km/h and higher can physically force ice to break up. Lake Simcoe, for example, has seen extensive rescues by helicopters when winds have broken off ice in sections as thick as 10 inches. If high winds are forecast, stay home.

Death of surface ice

Temps (above 45 ̊F) can remove two to three inches of ice in a day or two. A week can easily remove six to 10 inches. Shorelines always break up first due to radiant heat energy on rocks, sand, and mud.

Internal ice degrades at a slower rate. Sunlight in late March reduces thickness, but mostly degrades the integrity (strength) of ice. The ice will become porous, honeycombed, and dangerous.

Thaw conditions can occur anytime during the winter. Thawed weak ice can be either white or light or dark grey.

Fishing new ice

1. Check ice thickness, preferably with an ice chisel, as soon as you leave shore. Ice will get thinner as you move farther from shore.

2. As a group of two or three people, move out in a line spaced apart with a trailing rope from the first to last person. Check ice thickness frequently. Ice thickness and quality can vary by two inches over as few as 50 feet.

3. Watch and listen for cracking ice. Hearing this requires an immediate check, but “quiet ice” could mean:

a) Good, cold ice over four inches thick, with not too much stress

b) Warmer ice under two inches thick, very dangerous

Breakthrough thickness

Breakthrough thickness is defined as the threshold ice thickness of strong black ice required to support an angler of a specific body weight, including clothing and gear.

Extensive testing indicates a 170-pound individual with 10 pounds of clothes and backpack will achieve minimum suspension at 1.1 inches of ice thickness.

Most guidelines recommend not venturing out on foot without at least four inches of good ice.

All lakes have a current flow, however minimal. The water directly under the ice sheet is near 32 ̊F, but two or more feet under the transition layer, the temperature can be two-to-three degrees warmer.

When water is forced over an underwater shoal or between two narrow areas of land such as shore and an island, the warmer water is forced to the surface and inhibits maximum ice formation. Ice cover could be only one third or less of what the adjacent ice thickness is.

How to self-rescue

Don’t panic if you break through. Try to remember these steps which you can rehearse mentally:

1. If you break through, try to quickly cover your mouth and nose to avoid the gasp reflex and prevent inhaling water.

2. Paddle your arms and turn to face the side of the hole that you were walking on. That side is thicker ice and is your way out.

3. If you’re wearing a backpack, get it off and throw it on the ice. Its weight will drag you down. Get your ice claws/picks from your lanyard, one in each hand.

4. Get your elbows on the ice and start kicking your feet dog-paddle style to raise your lower body to the surface.

5. Now use frog-like kicks to push your chest up on the ice. If you have claws, sink them in and pull.

6. If the ice breaks, don’t panic. Try again until the ice supports your body.

7. Do not stand up, but rather roll or crawl until you can stand up safely.

8. Get warm as quickly as possible to avoid hypothermia.

Float suits. Worth it?

Insights from Dr. Gordon Giesbrecht, a professor of thermophysiology at the University of Manitoba and a coldwater exposure expert.

Treading water: Cold water incapacitation occurs five to 15 minutes after immersion as muscles become too cold to tread water. This accounts for 60% of mortality, but with flotation suits, that figure is reduced to 20%.

Cold shock: Cold shock from immersion in the first couple of minutes from inhaling water or heart problems caused 40% mortality, but only 10% mortality with flotation suits.

Hypothermia: Hypothermia with survival/flotation suits does not occur for an hour. This provides rescuers a window of opportunity.

Ice essentials

Ice chisel: Use it to probe for thin ice. The chisel can also be used as a walking stick or for leverage when climb- ing out of a breakthrough.

Ice claws: Essential for self-rescue. Experts estimate that over half of all ice breakthrough deaths could have been prevented with claws.

Nylon rope: A 50 foot length of 1⁄2-inch nylon rope is ideal. When walking, attach one end to yourself and the other to your sled or fishing partner.

Flotation suit: They save lives.

Ice cleats: These over-the-boot harnesses grip the ice and are critical in avoiding slips, falls, and serious injury.

Originally published in the Nov.-Dec. 2020 edition of Ontario OUT of DOORS Magazine

Leave A Comment