Summer. Iced tea on the dock. Siestas under the big willow tree. Air conditioners humming. Nothing moves too fast during the hot days of late June, July, and August, at least above the water. Down in the lake, things are a bit different.

As the long, sunny days and mild nights take effect, weed growth blooms and water temperatures rise. Perch, walleye, crappie, and bass respond by feeding actively, darting after minnows through thick cabbage beds and around wave-tossed reefs.

Small broods of ducklings work quietly along shorelines, their tiny feet kicking excitedly below the surface. The hens look on nervously, aware that danger awaits above and below.

Along the weed cover and the edge of shoals, muskie lie motionless, their eyes watching keenly for movement. Far from being sluggish, fish are energized by the warmth of the sun, and small fish or fowl moving within striking distance never know what hit them. Muskie strike with incredible speed and power, leaving nothing but a swirl and a puff of scales or feathers behind.

So why do so many of us have such a tough time catching these savage predators? And why do they so often reject our offerings at the last moment? Since I’ve done most of my muskie fishing during summer, with some of the finest muskie anglers in Ontario, I’ve had ample chances to get these questions answered. The revelations have come slowly, but steadily.

Weather patterns have proven to be a major factor. And, I fish solid, black lures with growing confidence. But in the long run, when the chips are down, I believe the most vital component to consistently triggering and catching summer muskie is speed. Muskie live in the fast lane.

A case in point. It’s a torrid summer evening on Lake of the Woods. A long day of throwing jerkbaits along the edges of deep reefs pays off with a big, fat zero. My shoulders, sore from pulling 10inch (25 cm) chunks of 1″ wood, are the colour of boiled lobster. Nothing is moving, at least on the reefs, where we assume muskie will be holding in the oppressive heat.

As the day wears on, we head to a weedy island saddle that has given up a few big fish in the past. We work it over with every conceivable bait. The clock keeps ticking. I dig deeper into my muskie tackle, and an unused black marabou bucktail stares up at me from the bottom of the Styrofoam cooler.

With nothing left to lose, I clip it on and cast. The two gentlemen in the boat with me nearly fall over as the feathery spinner drops to the surface and floats. However, a quick jerk of the rod drowns the bait, and it rides nice and high over the weeds. On the next cast, I try a trick learned a year before and start my retrieve before the spinner hits the water. I speed up the retrieve and the marabou pulsates temptingly, the blade bulging the surface and creating a long ripple. As it nears the boat, a muskie appears out of the weeds and clamps onto the black mass of feathers and hooks.

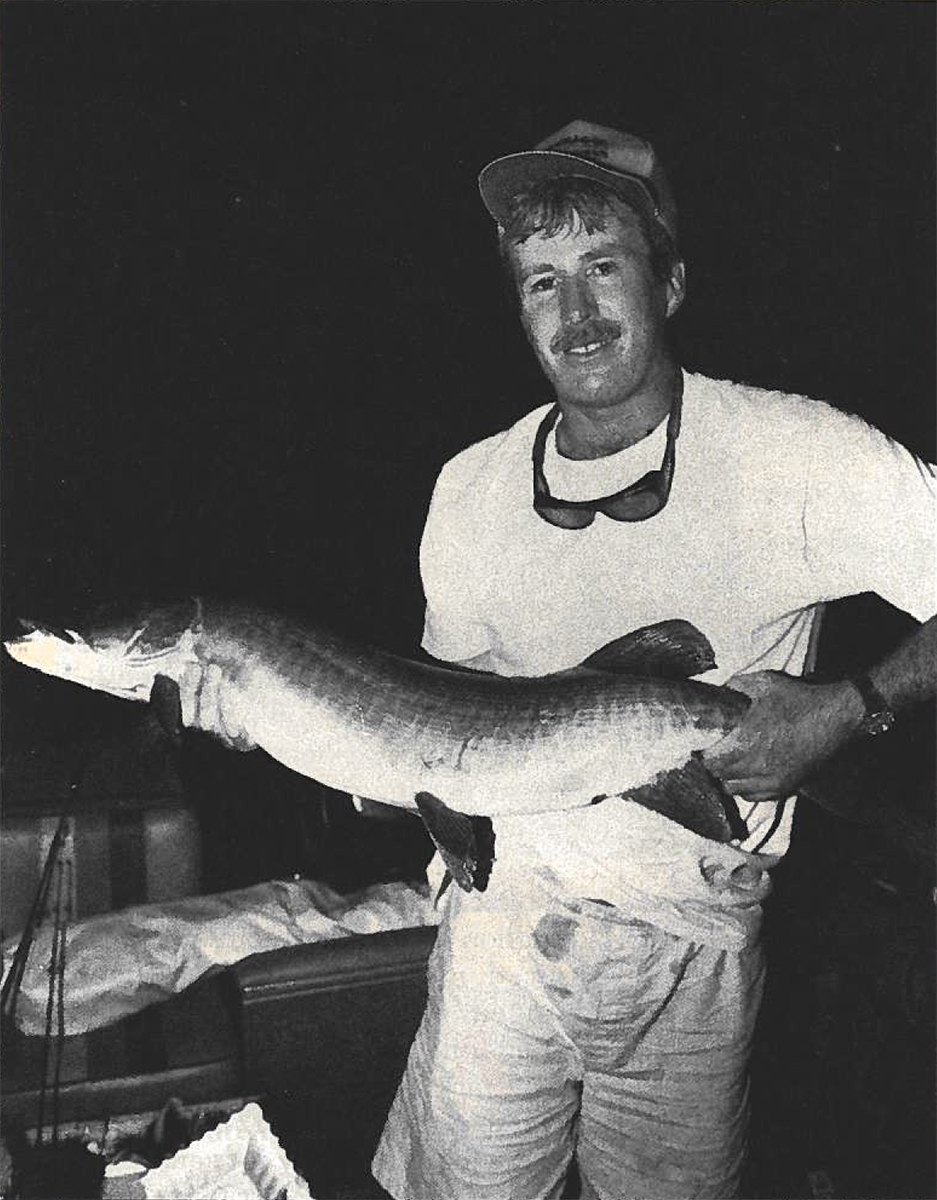

The calm lake surface is shattered as the 4 foot long (1.2 m) beast spirals into the weeds, trying vainly to shake free the feather duster. The fight is short, but eventful, and soon almost 30 pounds of muskie is lifted into the boat. Success at last.

Now, almost every muskie hunter has heard that you have to retrieve a bucktail fast in summer. But there’s fast, and there’s FAST! Sometimes it takes a little extra fire in the blades to stir up the big fish.

This point was further driven home to me a few years back, when I fished with Colin Grant, a Kenora-area muskie angler renowned for his muskie lure, the Grant Bait, and for catching trophy fish. Although Colin’s lure is a jerkbait, during our mid-August trip he clearly preferred to burn bucktails over weeds and reefs for summer muskie.

To get just the right twist to his spinners, Colin replaced the blades with silver lake trout spoons. He said they caught more water, which caused the bait to ride up and chum the surface at high speeds. He also stressed that engaging the spinner before it hit the water was important to triggering muskie. Despite that often espoused theory that muskie over 30 pounds don’t move fast, Colin was convinced that you could not retrieve a bucktail too quickly for them.

Buzzing bucktails along the tops of weeds is one way to trigger summer muskie, but what about when the fish are not in the weeds? A certain percentage of them will always stay deep, and many even suspend in depths of 40 to 50 feet (12.2 to 15.2 m) while feeding on cisco, perch, and whitefish. This is where speed-trolling comes in.

Like many muskie anglers, I once felt that trolling meant long bouts of slow, monotonous dragging, and eventually a sore bum. However, a few years back, a lodge owner on Little Vermilion Lake, near Sioux Lookout, showed me a trick that forever changed my concept of muskie trolling. Bill Erdmenger used relatively light tackle for muskie, a medium action spinning rod and 12-pound-test line. He felt that heavy rods and foot-long lures were overkill for the majority of muskie he caught. To prove his point, he clipped a #5 gold Shad Rap onto his steel leader and flipped it overboard.

He then gunned the out-board, watched until the tiny crankbait was right on the edge of flipping over, and proceeded to let out a whole bunch of line. We trolled so fast that a fellow muskie fisherman would later comment that we “looked like we were water skiing out there,” but Bill seemed confident. Sure enough, about two-thirds of the way down the weed bed, his rod slapped down as a muskie inhaled the speeding lure.

For the next five minutes, the fish plowed through the weeds like a tractor, doing all it could to try and break the relatively slender mono that threatened its freedom. Bill carefully played out the fish, and we finally netted the 42-incher (107 cm), the little Shad Rap barely a speck in its toothy mouth. That fish could have been written off as a fluke, if we hadn’t managed to catch a handful more muskies and some fat pike during the next few days while using the same technique. I was sold.

Why a 20-pound (9 kg) muskie would bother with a little crankbait is an interesting question. Certainly it flies in the face of the belief that large fish won’t bother with small bait. Keep in mind that Ken O’Brien’s Georgian Bay brute was caught on a tiny Countdown Rapala. I don’t subscribe to the theory, spread by sheepish muskie men, that O’Brien’s 65-pound (29.6 kg) muskie was yawning and just happened to inhale the passing lure. Certainly the speed of a crankbait triggers the strike mechanism in these fish. And who knows, maybe big lunge just like a good chase every once in a while.

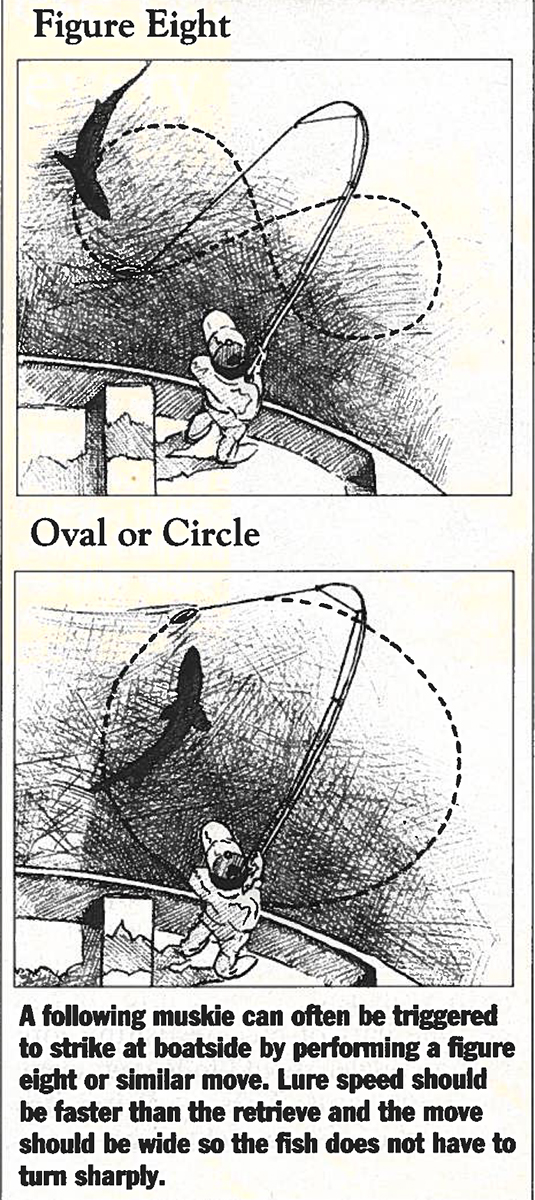

No discussion of triggering muskie with speed would be complete without touching on the figure eight. For those who don’t know, this move is performed by jamming your rod tip into the water at boatside and tracing a figure eight with your rod tip and lure. It has become part of muskie fishing lore that an angler should follow up every cast with one. This tradition has merit, but a figure eight done at the same speed as the retrieve will certainly not excite a muskie to strike. Nor will a movement done so tightly that the fish is unable to turn and strike the bait. But done properly, the figure eight can trigger hard strikes from muskie that were only half-heartedly following. It’s a technique worth practising.

One of the more efficient practitioners is Bill Friday, a muskie man who parks his rig in Kenora. Last year, during an unusually slow day on Lake of the Woods, Bill saw a big muskie move lethargically out of a shallow weed bed and set up slowly behind his Eagle Tail bucktail. Bill crouched and, with both hands tight on his rod butt, began working the bucktail with large, exaggerated sweeps. “He’s still there,” he groaned, picking up the pace. As the seconds rolled into a minute, Bill continued to chum the water with his rod, creating a whirlpool at boatside. I could see the muskie, obviously excited by the ever-increasing speed of the blade, turning behind the big spinner. Directly under the boat, the fish finally saw red and crushed the bucktail. In a split-second move, Bill set the hook, sprung up, and hit the reel release, as the fish corkscrewed on the surface. It was a 45-inch (114 cm) beauty, a hard-won fish that turned out to be the only muskie of our three-day trip. The aggressive figure eight had paid off.

Performing the figure eight at high speeds is not easy; you have both the drag of the rod and the lure to contend with. And the position of your arms at boatside is usually awkward. Because of this, your natural instinct will likely be to make the figure eight smaller, to cut down on friction. The problem is that muskie are designed to attack in bursts of speed, generally in a straight line. They also have a blind spot directly in front of them, which accounts for the missed strikes and snapping they often exhibit when pursuing a bucktail or jerkbait. Because of this, the larger the figure eight, the better the odds of a hookup, as it gives the fish a better chance to get its bearings and find the lure. Some muskie anglers prefer to use an oval or circular pattern.

I suggest trying both patterns on any muskie that can’t make up its mind. Just keep the speed as fast as you can muster. Remember, you’re fishing in the fast lane.

Originally published in the June 1993 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS magazine

Leave A Comment