I think many of us would agree that the most important moment in any bow hunt is the shot. For this is the culmination of your efforts. It’s where the rubber meets the road.

Make a good shot and you’ll leave the field with venison. A bad one means you’ll walk away with nothing but regret.

The shot is a simple, intuitive thing. Yet it is also one that requires a solid foundation built upon sound judgment, composure, and a few good decisions. All of these components need to come together when opportunity knocks.

No time for nerves

Nervousness, I believe, is the cause of many blown opportunities. It’s why good archers make bad shots on deer at ranges they routinely destroy nocks at.

Nervousness is insidious. It can cause a bowhunter to forget their plan and make rash decisions, such as moving too soon or taking less than optimal shots. It can introduce indecisiveness and doubt where immediate, decisive action is required.

Most hunters I know, experienced or otherwise, concede that a mature deer will, at the very least, cause their heart rate to elevate. This is natural — a deer is a majestic, cautious animal and this is what you have been dreaming about all year. Bowhunting is a one-shot, close-quarters game and when a deer is approaching, the pressure is on.

To fill that tag, you need to master your nerves.

If my nerves are getting the better of me, I think, “It’s only a deer; calm down.” Then, I go through my pre-shot checklist. When should I draw? What’s the range? Where will I aim? What shot angle should I wait for? And so forth.

My checklist is established the minute I sit in the stand. I’ll range trees, rocks, fence posts, or other landmarks so I know how far a deer is when it reaches those points. I’ll also survey possible approaches and determine where I will have my best opportunities to raise my bow, draw, and shoot. For instance, the minute a deer’s head passes behind a big tree over there.

When I do these things, I’m too occupied to be overly affected by nerves.

You might be affected very little. But if you are, find a way that helps you master your nerves.

Jumping the string

This phrase describes the action a deer that has seen or heard an arrow launch will instinctively take. The deer basically lowers its body in the blink of an eye to load its legs in order to bound off. A deer that jumps the string typically ducks under a passing arrow or gets hit too high.

Some archers deliberately aim low if they feel a deer is suspicious and ready to jump the string. They’re hoping that when the deer lowers itself to spring off, their arrow will find the right spot.

I’m not a fan of this tactic because you’re essentially aiming off in hopes that the deer will move in the right place. It’s a risky proposition.

The aim point

The biggest concern new hunters have is where to shoot on a broadside or quartering-away deer. Obviously, anywhere that results in an arrow penetrating through the heart lung area. You don’t want the shot too high or too low, so aiming one third to midway up the chest area is perfect. The best advice I ever got is to line up my shot so it exits at the deer’s front leg on the far side. If you always keep that in mind, you’ll always have a shot that will pass through the deer’s “boiler room.”

Find a well-defined spot over your point of aim to keep from drifting off it. This could be a tuft of ruffled or darker hair, a bald spot, or some other mark. A definite aiming point ensures you are more accurate and are taking advantage of the aim-small, miss-small axiom.

There are other parts of a deer’s anatomy that, if arrowed, would cause quick death, but I don’t suggest you try those shots.

Here’s why. You can be off four inches or so in any direction, if you aim for the centre of the heart/lung area, and still kill a deer quickly. But, if you are off the same distance on say, a carotid artery on the back ham or a spinal column shot, you have wounded or, hopefully missed, a deer.

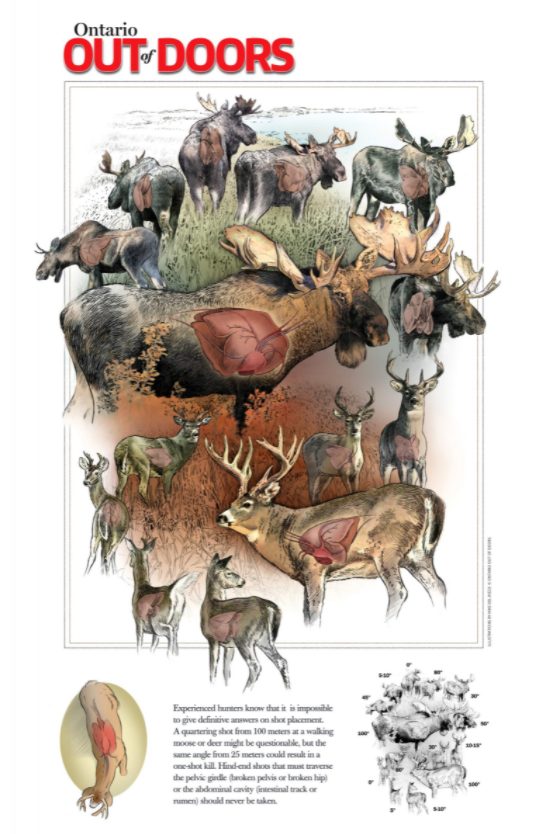

Click here to download the shot placement poster.

A calming influence

Sometimes, the deer is the nervous one. It might have seen, heard, or scented something it didn’t like during its approach.

If so, it’s best to remain still and allow the animal time to calm down. You shouldn’t shoot at a jittery deer. They’re the ones most likely to “jump the string” (see below) or bound off at the first sight or sound of you drawing or readying for a shot. The result could be a clean miss or a bad hit.

How do you know the animal is nervous?

It might constantly stop to survey its surroundings and scent the air for long periods of time. It might lower and raise its head repeatedly while eating in an effort to catch you moving. It stomps, snort-wheezes, or acts skittish.

Meanwhile, a relaxed animal walks in normally.

Sometimes, if you sit still and wait it out, a deer on high alert will eventually relax. That’s when you should take the shot.

If you must take a shot at a deer on high alert, however, never do so when it is looking at you. A suspicious deer looking at you will almost certainly try to duck your incoming arrow. And that can end with disastrous results.

Bright moves

For a good shot opportunity, your quarry must be positioned in the right place. I know: any location within effective range is the right place so long as you have a clear shooting lane.

That’s true — unless the sun is rising or setting right behind the deer.

Placing crossbow crosshairs or a sight pin on a deer backlit by a glaring low sun that’s either rising or descending over the horizon can be problematic.

You can avoid this by setting up with sunset and sunrise in mind, too. Once you know where you expect to intercept deer (at a bait pile, oak tree, a split in the trail, a gap in the fence, etc.) you should position your stand to cover it with wind direction as well as sunrise and sunset in mind.

Optimum range

The best shot you can hope for is one well within your comfort zone, but not so close that drawing and aiming will be detected.

For most of us, that’s somewhere between 10 and 25 yards with a vertical bow and maybe out to 40 yards or slightly more with a crossbow. But situation and terrain can affect this. You might be hard pressed to get a 25-, or even 10-yard shot, in a balsam-filled area. Likewise, you might be able to fling an arrow 80 yards across an open field — which, by the way, doesn’t mean you should.

Some hunters are tempted by longer shots because they have mastered them at the range. These shots work just fine on occasion. What you should keep in mind, however, is that the chances of recovering an arrowed animal decrease significantly the longer the shot distance. The reasons include decreasing accuracy at longer ranges, reduced arrow penetration, greater margin of error when estimating range, more opportunity for the animal to move during arrow flight time, greater effect of wind on the arrow, unseen vegetation causing deflection (such as overhanging branches that might be in the way of the arrow’s trajectory), and more distance between the hunter and first signs of a blood trail.

For all these reasons, I’d advise any bowhunter to wait for a closer shot.

Playing the angles

OK, let’s assume you have. You’re calm, ready, and an unsuspecting deer is offering you an unobstructed shot at confident range. Now, you just need to wait for the right shot angle. Patience is required at this stage.

Ideally you want a broadside or quartering away angle. This provides very good exposure of the heart/lung area.

Of the two, I prefer the angling away shot because it allows your arrow to travel through a greater cross-section of the deer. (See “Far-side geometry”.)

This shot also provides a better margin of error. If your arrow hits a little far back, it will still probably pass through the liver and lungs because of the angle of entry.

A steeply angled shot from a tree stand also provides a longer wound channel. This shot also produces a low exit hole, which means a more immediate blood trail. Combine a quartering away shot that lands in the heart/lung area with a steep downward angle and you’ve got mortally wounded deer that’s going to be very easy to track.

My experience has shown that deer I shoot from ground blinds do not leave initial blood trails as quickly, though they expire just as fast. I’m guessing this happens because the entrance and exit hole is basically on the same level and it takes a little while for the bottom of the lung to fill before good amounts of blood leave via the wound. Don’t get me wrong; blood trails happen. They just don’t happen as quickly as from the tree stand shot previously described.

There are other shot angles that will allow you to inflict a humane kill, too. The problem is those aiming points are smaller and far less forgiving.

Far-side geometry

To get a sense of the advantage an angled shot can give, imagine the deer’s chest cavity.

If you were to pass an arrow through the cavity at a completely perpendicular angle, it would cause damage over the entire wound channel, which would, of course, be devastating and lethal.

Now pass that same arrow from the rear portion of the chest cavity on the near side, to the leg on the far side, which is at the front portion of the chest cavity. Clearly, this produces a much longer wound channel, which means even more bleeding, and destroys a longer cross section of vital organs. A deer hit this way, is dead on its feet with some added forgiveness should the arrow enter a little further back than intended.

Posture

The deer’s posture also needs to be considered. For instance, it’s far better to shoot at the deer’s heart/lung area when its front leg on the near side is extended forward. This moves its shoulder further out of the way, which is key because, as previously mentioned, the shoulder blade and muscles can shield the vitals and reduce penetration.

Another ideal posture is the deer is facing away. If the deer does not have a direct line of sight to you due to a tree, rock, or other obstacle that’s also good. Similarly, I’d rather have a deer standing rather than bedded down because it exposes more vitals that way. Lastly, it’s best to shoot at a motionless deer.

A quick background check

Make sure another deer isn’t behind the one you want to shoot at. This can be an issue, especially for those who are shooting from ground blinds at deer over bait. Pass-throughs are common with modern gear and this can result in an inadvertent hit on an unintended animal.

Last season, I had an opportunity to place a crossbow bolt through a buck that was walking directly towards me. This is not normally a shot I’d take but it was less than 10 yards and I had a good scope on a very accurate crossbow, so I knew I could place my shot perfectly, which is to say, low in the centre of the chest in order to penetrate into the heart-and-lung area. I did that and the deer expired quickly, within 20 yards.

During field dressing, I expected to find my bolt inside that animal but it was not there. The next day, I returned and found the bolt almost fully buried in the dirt 10 yards past where I shot the animal. That bolt had passed through the entire length of the buck, exiting just below the rear ham. Had another deer been following it, this could have been disastrous.

Deer in the background are easily seen from an elevated platform, but not always from the ground. So, look carefully, and if one is there, wait till it isn’t.

Finally

Despite our best-laid plans, deer hunting remains a game full of unexpected events and surprise endings. You can’t control what a deer ultimately does. At best, you can influence behaviour and make predictions based on past experience, accumulated knowledge, and good scouting.

When it comes to the shot, however, you have control. All you need to do is practise regularly and be aware of the ways to up the odds in favour of that one perfect shot. That way when opportunity knocks, you’ll be ready and able to make the most of it.

Originally published in the July 2020 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS.

Leave A Comment