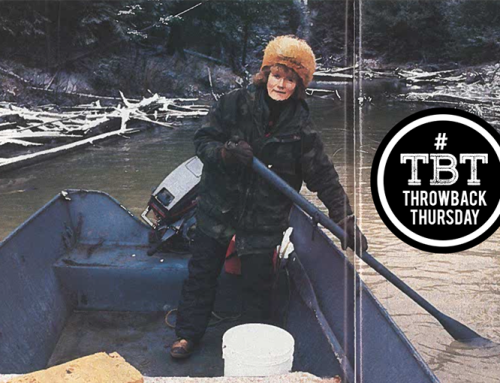

With the morning sun painting streaks of light on the autumn-coloured hills surrounding Algonquin Provincial Park’s Tanamakoon Lake, I try to simulate the moves of Frank Kuiack steadily pumping his wire trolling line. Looking like part of the landscape, weathered countenance under a leather fishing hat and a home-rolled cigarette dangling from his lip, he sets the hook into what turns out to be a small, brightly coloured lake trout. It’s the first I’ve witnessed caught in the park, but certainly not the first for Kuiack.

He’s been catching fish in Algonquin for more than 70 years and guiding others for almost as long. Now in his 77th year, Kuiack is as busy as ever guiding clients from Europe, Asia, Australia, and the US, including a long list of Hollywood stars and politicians. It’s the third week of September and I’m here to experience what so many have over the past decades in Algonquin, a few days on the water with Frank Kuiack. Joining me is my friend Jack Mihell.

Once a forester in Algonquin, Jack lived just up the street from Kuiack in Whitney and the two became friends. Now living in Sault Ste. Marie, Jack usually gets out once or twice a year with Kuiack and invited me along. “Can you guess which house is Frank’s?” Jack asks, after our drive through Algonquin and on to Whitney.

I choose the timber-frame house with moose antlers under the roof peak and a collection of boats and canoes in the yard. Completing the scene is a small man in a brown jacket and work pants. Lean and wiry, with a broad grin and generous laugh, Kuiack extends a thick hand and a welcoming smile.

Early to bed, early to rise

It’s 5 am when I crawl out of bed and into the living room, where Kuiack sits at the dining-room table in blue work pants and shirt, sipping instant coffee from a cup that says, “Of all the Old Coots in the World, they say I’m the Cootest.” A halo of smoke rises from a hand-rolled cigarette. “Good afternoon,” Kuiack says, laughing and nodding towards my threadbare red long johns. “I think we shop at the same place.”

Anytime I encounter an older person doing what they love and showing no signs of slowing down, I try to figure out what keeps them going. I’ve never considered heavy smoking as part of a healthy lifestyle, but when Kuiack springs up from the table and launches a handful of bacon into a pan of hot lard, I’m left scratching my head.

Looking for trout

We jump into Kuiack’s van and head up still-dark Hwy. 60, where a trail heads up about a half-mile to a small splake lake. I carry the canoe and follow Kuiack, who’s lugging our fishing gear in a large canvas-framed pack up a slight incline through a mature hardwood forest. He sets a blistering pace for three-quarters of the way, then stops.

He recently had an operation to install a fake artery the entire length of his leg. “Now, the other one is starting to go,” he says, annoyed, as he regains circulation with a short rest on a stump.

It’s been a warm fall and my expectations for good trout fishing are low. I know the water is still warm and the fish will be deep and inactive.

Kuiack knows this, too, and sets up Jack with a wire line, while he and I troll with spinning gear. The morning is sunny and calm, and the sloping rock shoreline features the legendary fall colours of Algonquin. But, by 11 am we haven’t had a bite. We decide to switch gears and head back to the van.

“Want to see Jack’s eyes light up?” Kuiack asks with a wink, as he pulls a piece of leftover chicken from his pack. Indeed Jack’s eyes do light up, but then, so do mine. We all nibble on chicken as we drive to the dock on Galeairy Lake near Whitney, with Kuiack flooring the van like a teenager.

But, bass will do

We pile into his aluminum boat and start picking off largemouth on crankbaits along a narrows, before working shoreline vegetation and patches of lily pads, where Kuiack consistently extracts the biggest bass. But, we’re on his home waters. He shows us the little peninsula of land where he grew up.

“Caught my first bass here when I was 4…on a safety pin and a piece of string,” says Kuiack, who was guiding by the time he was 8.

Much of what I know of Frank Kuiack’s early life comes from reading a book by Ottawa Citizen reporter Ron Corbett called The Last Guide, published in 2001. Corbett was researching a story on Algonquin wolves, met Kuiack, and their relationship culminated in a book on his life that’s been translated into three languages and has sold more than 240,000 copies. The book offers a glimpse at the early days

of fishing and guiding in Algonquin, chronicling Kuiack’s development as a guide, as a hard drinker (he’s been sober now for more than 20 years) and as a husband to his now-deceased wife, Marie.

Guiding for life

A decade after the book was published, Kuiack continues to guide regularly. Aside from Sundays, when he doesn’t guide, he’s only had three days off this summer. This is at least partly due to the publicity generated by the book, with many clients wanting to fish, but others who simply want to see something specific, like a moose, a bullfrog, or fall colours.

As we cast into clumps of thick lily pads, I ask Kuiack about retirement, and I’m not surprised at his answer. “Oh, I will be guiding til I can’t do it anymore,” he says, simultaneously setting the hook into a beefy largemouth.

The sun, the calm, and the active bass continue through the evening. After eating only two pieces of bacon at 5 a.m. and a chicken wing for lunch, Kuiack admits to being a little hungry, and just before dark he suggests we head back to the house for supper.

Digging in

Barbecued steaks are complimented by Kuiack’s homemade horseradish and tomatoes from his garden. Dessert is cake, followed by a thick home-rolled for him, as he leans back in his chair, practising the guide’s art of storytelling.

“Here, drink this; you’re gonna need it,” Kuiack says, describing a time when he was staying in a cabin deep in Algonquin’s interior and a fellow arrived with a grisly wound from jumping on a large spike protruding from an old log dam.

“I knew I couldn’t get the plane in that night, so when the guy leaned his head back to drink, I poured the brandy on his wound…knocked him right out,” he says with a laugh, “…sewed him up with fishing line.”

But, most of the injuries Kuiack talks about are his own, the result of guiding and other occupations. In fact, he still fells problem trees, climbing and cutting them piece by piece from the top down. “Got hit by a really big limb six years ago,” he says, lifting his shirt to show a scar. “Lost a kidney.”

Back in the 1970s, he slipped carrying a load of moose meat, injuring his back. A 2-year rehabilitation included installation of four “swivels” in his back and a year in a body cast. He was once plastered against the roof of a station wagon when a tire he was inflating blew up, smashing his head and breaking both arms.

“Had to quit smoking for a few months,” he says, lighting another and moving on to more accounts of his experiences, including staking claims between Timmins and Hudson Bay in the 1960s and flying a bush plane throughout Algonquin.

History on the water

The launch into Cache Lake is near the site of the old Algonquin Park train station and the once elegant Highland Inn. The Ottawa, Arnprior, and Parry Sound Railway Line, built by lumberman J.R. Booth in the late 1890s, once ran through here. The Highland Inn, completed in 1910 and accommodating 150 people, was dismantled in 1957 and the last train left Cache Lake in 1959. Today, there’s a length of track, some old foundations, and an interpretive plaque to commemorate this chapter of Algonquin’s history.

“I started guiding here when I was 12…arrived by train,” Kuiack says, as we load our gear into the aluminum boat. It’s calm and there’s still a morning mist as we wind through narrows and bays to an old railway trestle, where huge moss-dappled timbers sag into Cache Lake. We immediately connect with bass.

The harvest continues after threading through a narrows into Tanamakoon Lake. As we work along the shoreline, it’s evident that I’m the client and Kuiack the guide. Several times I get hung up from casting too close to fallen trees or letting my line sink too long. Kuiack is extremely patient and manoeuvres the boat so I can free my snag. On the other hand, when his buddy Jack gets snagged, Kuiack explodes with good-natured ribbing.

With more than enough bass for shore lunch, we break out the wire line for lakers. Kuiack has already caught two trout before I successfully mimic his technique and set the hook into a small fish. I can’t feel much of a fight with the thick rod and wire line, and comment that a downrigger would be fun in these small trout lakes.

“I can’t stand downriggers,” Kuiack says. “Can’t feel the strike or nothing.”

Shore lunch

Just before the bow touches shore, Kuiack springs to his feet, jumping from seat to seat to shore with alarming agility. Jack unpacks Kuiack’s shore-lunch kit, while he cleans the fish. The bass are filleted on a board, but he stands to clean the trout, filleting and deboning as one might core an apple, thick, deeply calloused hands displaying remarkable dexterity.

Kuiack approaches the campsite with the fillets and promptly rearranges everything Jack unpacked, grumbling and shaking his head. He heats a pan of oil, a pot of water, and a can of beans on an old Coleman stove and then puts out cucumbers, tomatoes, bread, chips, and cookies.

When the fish is golden and the beans are bubbling, Kuiack picks up the hot bean can with his bare hands. “Can you take this for me, Jack?” he asks without flinching.

“Just set it on the table, Frank,” Jack laughs, obviously familiar with his trick.

Even though Jack and I ate a full breakfast, we’re starved. Kuiack passed on breakfast this morning, opting to fortify himself with coffee and cigarettes until noon, so we all fall vigorously on the freshly caught feast.

Looking back

After lunch, we revisit the bass of Tanamakoon and Cache Lakes. Our last stop is anchoring off a set of old submerged cribs near the launch ramp where the Highland Inn once stood.

Kuiack gives Jack a hard time for casting in the wrong direction. “You’re going to get snagged in those cribs,” he says gruffly, then lowers his voice, inflecting a distant nostalgia. “You should have seen the size of the dock here…there was a dance floor on top of the boat house.”

I’ve seen old photos of this once-elegant railway hotel. The Highland Inn, with its huge dock and boathouse, was an Algonquin institution that will never be replaced. And, as we angle with the park’s last full-time guide, I realize the same can be said of Frank Kuiack.

Originally published in Ontario OUT of DOORS’ 2012 Fishing Annual.

Leave A Comment