I cast a white and pink bucktail jig across the current from the stern of the 20-foot welded aluminum boat. Moments earlier, I had watched my angling partner, Storm Carroll, cast out a white streamer and connect with a large Arctic char. After a 10-second battle, the spirited fish spit out the hook and disappeared into the steely-grey depths. When my line goes taut, I’m able to angle the fish to a waiting landing net. I fumble for my camera while Carroll hoists my first ever Arctic char.

We are at the mouth of the Armshow River, about 30 kilometres southwest of the city of Iqaluit, Nunavut with Alex Flartey from the Department of Environment, Sara Acher from Nunavut Tourism, and Inuit elder Solomon Awa. As we admire the first char of the day, the tide is quickly retreating to expose the briny sand and boulder shoreline that cradles this swift flowing river.

Carroll and I are dropped off on shore where there’s more room to cast flies to the schools of char now working their way upstream. I tie on a white-bodied muddler minnow and by the third cast I’m setting the hook. Although at best the fish is 4 pounds, it fights like one twice its size.

Our time here is limited and I pause to soak it all in. Downstream, Carroll lays out a cast surrounded by the sparse and undulating rocky landscape of Canada’s Arctic. I notice the porpoising fish off a current-swept gravel bar and select a white and red streamer. It finds its mark first cast and for the next hour we tangle with char before the inevitable call to return to Iqaluit.

Before we depart, Awa comes ashore to fillet fish. “Any parts of the char you eat that we might not?” asks the ever-inquisitive Carroll. “The liver,” says Awa stuffing a piece of the reddish-pink meat into his mouth and slicing up a couple of additional pieces. Carroll and I pop the pieces of cold liver into our mouths.

Back to Iqaluit

We’re in Nunavut to film and photograph some angling opportunities around the city of Iqaluit for Nunavut Tourism. The territorial capital is a bustling place. Its predominantly dirt roads are busy with cyclists, ATVs, pedestrians, cars, and trucks. More than 7,000 people — approximately 65% Inuit — occupy the homes, businesses and large government office buildings. New housing developments going up on the plateau overlooking the city will help to accommodate Iqaluit’s growing population.

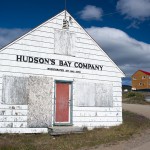

The unique Arctic architecture is decidedly angular and colourful, with all major buildings raised off the ground so they don’t disturb the permafrost.

We are staying in the Capital Suites, one of several large and luxurious hotels in Iqaluit. We have an adjoining room with a large living area and kitchen where I season a pair of meaty char fillets before laying them into a pan of hot butter. This is our first taste of fresh Arctic char and it’s one of the best fish I’ve ever tasted.

The community fishing hole

Next morning I call a cab, saying we want to go fishing. Within 2 minutes the driver pulls up in front of our hotel asking if we prefer to go to the pavilion or the golf course spot. “Pavilion,” I say and we drive a few kilometres west to the Gateway to Sylvia Grinnell Territorial Park where the Sylvia Grinnell River forks and flows over a twin falls before eventually merging with the saltwater of Frobisher Bay.

With a 12 metre tide — second only to Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy — the river below the falls changes from a series of pools and riffles to a still, deep bay at high tide. Just as at the Armshow River, we can see schools of char moving upstream over the shallow rocky bottom. However, these fish ignore everything we throw at them. As the sun gets higher in the sky, more and more people show up and soon the sun drenched rocks are lined with anglers.

Fires are built and coffee is perked as groups of family and friends settle in for a day on the river. It’s a friendly, social atmosphere along the river bank, where Iqaluit’s diverse population is apparent. In addition to Inuit, we meet people from Israel, Newfoundland, Quebec, southern Ontario, and British Columbia.

With these char running the gauntlet of big, flashy spoons, we’re confident we can find a finesse presentation they will hit with abandon. However, after casting just about everything in our fly boxes, our confidence wanes. The fish seem more curious than hungry.

When in Rome

Our next angling excursion is with Louis-Philip Pothier of Inukpak Outfitters. The Montreal native is a keen fly fisherman and takes us to a rock pier that juts into Iqaluit’s harbour, where Carroll proves particularly adept at catching sculpin.

When rising tide drives us from the pier we work our way upstream, well above the falls. Pothier says there are few fish above the falls in summer, but in September it fills with char in their spawning colours heading upstream towards Sylvia Grinnell Lake.

Back below the falls, we stop at a series of depressions along a grassy flat that Pothier says are the remains of subterranean dwellings from the Thule culture, evidence of their long history of seasonal occupation at the river mouth. However, one of our more fruitful discoveries is a 1-ounce Blue Fox Pixie lure Carroll finds in the shallows of the river. Later in the afternoon we cast into the rising tide below the falls and Carroll manages to hook 5 fish on that very lure. We keep a 4-pounder for dinner.

Over the next few days we hook a few fish on flies, but spin casting the locally-favoured big, flashy spoons is the most reliable presentation for this unique urban Arctic fishery. Less than 3 hours flying time from Ottawa, Iqaluit is probably the only city where anglers can catch Arctic char a short walk — or cab ride — from their hotel.

I can’t help wondering about the wealth of opportunities that must await anglers in some of Nunavut’s more remote destinations.

First published in the 2014 January-February issue of Ontario OUT OF DOORS.

Leave A Comment