Photo courtesy of Jens Lambert Photography

Perplexed by a particular tom that ignores your calls, even when there isn’t a hen around? Does it turn tail and go the other way? And, just when you’re ready to buy a new turkey call, does a different bird respond to your putts from 200 yards away?

I’ll bet there’s a good chance you wrote the first bird off as call shy or extra wary. And you wouldn’t be alone.

The call-shy, hunter-avoidance debate is a common topic when turkey enthusiasts rehash their hunts. Some believe if the calling is bang on, it will neither scare a turkey nor make it wary. Others argue that experienced toms can tell the difference between a human call and a turkey, and that hunter disturbance can put birds on alert.

Now, science may have put that debate to rest, or at least weighed in on it.

A study out of the University of Georgia, entitled Influences of Hunting on Movement of Male Wild Turkeys during Spring, determined that hunters do have an effect on turkey behaviour. The research was undertaken by UGA researchers John T. Gross, Bradley S. Cohen, and Michael J. Chamberlain, and Louisiana State University’s Bret A. Collier and was presented at the 11th National Wild Turkey Symposium last year.

In areas where hunters got to within 100 metres of the turkeys, the birds increased their core area of use. The distance between the weekly core centres also increased. Turkeys that experienced hunters from distances between 100 to 300 metres used smaller core areas.

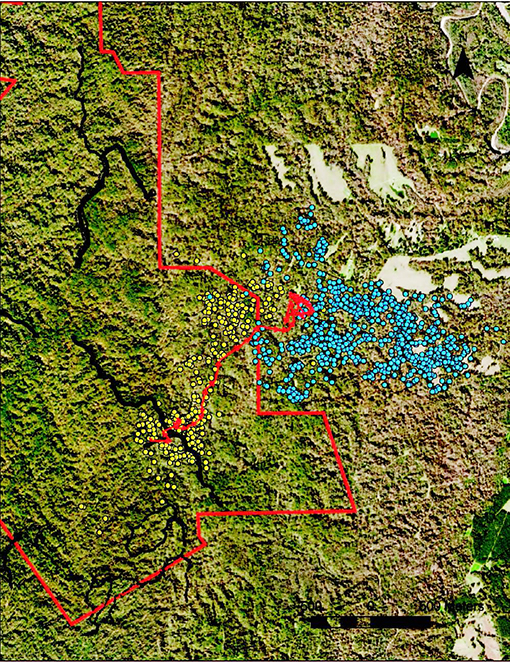

A depiction of what the study’s authors speculate to be a male eastern wild turkey avoiding hunter activity by leaving the management area on opening day of hunting season in Louisiana. Yellow points indicate the turkey’s locations from Feb. 15 to March 16, 2012, the red line with arrows shows the turkey’s movement path on March 17 (opening day), and blue points indicate the turkey’s locations from March 18 to April 7, when it was killed. Black lines are the hunter track logs recorded with handheld GPS units on opening day. Diagram courtesy of University of Georgia

GPS tracking increased the accuracy and understanding of turkey movements over previous studies, which had shown that some birds moved when turkey season opened. This was the first study to use GPS technology on both hunters and male turkeys.

The study’s monitoring took place in a public hunting area in Louisiana, where hunters were controlled and outfitted with handheld GPS units that tracked their movements. On the turkey side of the equation, 12 male turkeys wore transmitters.

Of the turkeys with transmitters, seven were killed by hunters. Those that were harvested were exposed to fewer hunters within 100 metres of them than those that both survived the season and experienced hunter proximity between 100 and 300 metres.

“Our findings suggest that it may be easier to harvest turkeys that experience less hunting pressure, whereas turkeys experiencing great pressure may learn to avoid hunters,” wrote the study’s authors.

They also emphasized that the response to hunter presence varied between birds, and overall, the effects were minor. For instance, one bird left the wildlife management area on opening day of hunting season and didn’t return, while most had less than 10% change in distance travelled.

“Turkeys that survived the hunting season tended to more often encounter areas of greater hunter presence, suggesting a learned anti-predator behaviour.”

The study’s authors also suggested the possibility of all turkeys in heavily-hunted areas being, “relatively experienced and difficult to harvest.” They put forward that a possible solution to relieve pressure on heavily-hunted public areas would be to rotate closed and open sections throughout the season.

Northern birds

So what does this mean to Ontario hunters? Do Ontario turkeys react in the same way as the birds in the southern United States?

Dave Reid, who was involved in the wild turkey reintroduction in Ontario, and who is a die-hard turkey hunter, believes in call shyness and wariness in some birds.

“If they had a bad experience and got called in, I think there is a certain amount of learned behaviour with them,” he said.

In the early days of the turkey program, there was extensive trapping and transferring of turkeys within the province to establish new populations. The birds were lured into the trap site with bait, but Reid said some birds still became trap-shy.

Some of the initial turkeys trapped were from a Missouri ranch where they had been hunted hard, while others were their offspring.

“There were differences between the locally raised birds and those from Missouri,” he said. Reid’s observations back what the study found. The turkeys that saw more hunting pressure in Missouri were warier than birds born in Ontario that hadn’t yet been hunted.

Personally, I have noticed birds becoming more elusive after the opener on properties where there is pressure from other hunters. As the season progresses and the other hunters give up, the birds return to their normal behaviour.

So now what?

With this new knowledge, should we re-examine our approach to hunting? Generally, I think the answer is no, as the study found not all birds are created equal nor are as wary. But, in the case of the hunter after a large wary tom or hunting a property with heavy hunting pressure throughout the season, perhaps new techniques should be tried.

This can be as simple as approaching the bird from the opposite direction of most approaching hunters, patterning the bird, or calling from a greater distance.

So has this study put the debate about call-shy and wary birds to rest? Not likely; it’s a good bet call shyness will continue to be talked about for as long as hunters sit around coffee shops and hunt camps telling tales of the day’s adventures.

This article first appeared in the April 2017 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS magazine.

Leave A Comment