In the fall of 2004, shortly after sighting in his new Beretta slug gun, my father-in-law (and hunting buddy) unexpectedly passed away. With his wife in shock and the family in distress, I offered to look after his firearms. I already had my Possession and Acquisition Licence (PAL), so I sought direction from the Canadian Firearms Program (CFP). My father-in-law’s executor provided them with proof of executorships, a copy of the will, and the death certificate.

Over the next year, I transferred some firearms to his eldest licensed son. The remaining firearms were temporarily transferred to me. Another son acquired his PAL. I then transferred them all to him, except the Beretta! I realize now that my father-in-law had begun passing on his favourite firearms years before his death.

Thanks to his planning, and the Canadian Firearms Program’s guidance, I was able to transfer his remaining firearms in a safe and relatively stress-free way. I gathered a spread of knowledge about passing on your guns. Here is what I learned.

Develop a plan

One of the most thoughtful things you can do for your loved ones is to plan for the dispersal of your firearms should you be unable to do so.

Your PAL is essential to the development of an estate plan, so make sure it’s renewed every five years. And if you move, notify your provincial CFO within 30 days. If you own firearms, but aren’t licensed, then you’re in illegal possession. For the sake of your spouse, executor, and inheritors who shouldn’t have to deal with that complication, take the Canadian Firearms Safety Course and get a PAL.

Take inventory

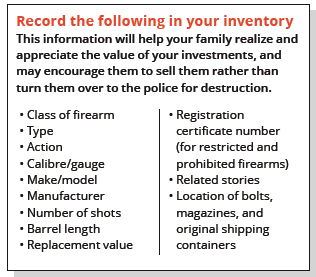

Wes Winkel, manager of Ellwood Epps gun shop near Orillia, encourages gun owners to maintain an inventory or catalogue of their firearms, including current values. The inventory information must be recorded on a piece of paper or in a digital file, such as an Excel spreadsheet.

If you legally own restricted or prohibited firearms, the registration certificate of those firearms will contain detailed information. To get an idea of the fair market value of your firearms, check out a gun shop website (or several) that has online sales, like Ellwood Epps, or review the results of a gun auction website, such as Switzers Auction.

What to do with the guns

This might be the most challenging part. Do you want your firearms to go to relatives and friends? Donated to a museum? Sold? Each option has its advantages and disadvantages.

If you decide to bequeath guns to family or friends, talk to them first to confirm they want them. And you don’t have to wait until the firearms become part of your estate to transfer them.

Dwight Peer, Chief Firearms Officer (CFO) for Ontario, advises potential recipients of long guns who aren’t already licensed to start the process of registering their guns. This way, everything is in order when the time comes to take possession of the firearm.

PAL needed

Since the recent passing of Bill C-71, anyone wanting to acquire a non-restricted firearm must be verified as holding a valid PAL before the ownership can be transferred. To do this, contact the CFP at 1-800-731-4000. For restricted firearms, recipients have to hold a valid restricted version PAL. Upon taking possession, recipients will also need to obtain a registration certificate for each firearm and an Authorization to Transport (ATT) from the CFO.

Gifting or transferring prohibited firearms is sticky. “Grandfathering” provisions may further complicate the process. Qualified gun owners and their executors are encouraged to seek counsel from the CFO. Officer Peer adds that individuals under 18 years of age are not permitted to acquire firearms by any means. This includes even as a gift. However, a youth at least 12 years old who holds a minor’s licence can borrow non-restricted firearms for specific purposes. If the prospective heirs to your firearms live abroad, contact them to see if they can legally own firearms in their country.

Wes Winkel further warns that guns exported must be physically stamped, which decreases their value. For more information on exporting firearms contact Global Affairs Canada at 1-800-267-8376.

Arrange for deactivation

If family members wish to keep a firearm without licensing it, you can arrange for a qualified gunsmith to permanently deactivate it. This entails irreversible measures like welding firing pins and rods in barrels, which can be costly.

Photo documentation of the deactivation process must be submitted to the CFO for final approval. Once deactivated, the gun is not considered a firearm. Under firearms laws, antiques are not considered firearms and do not need to be deactivated. Refer to the CFP fact sheet on antique firearms for details.

Handling a private sale

You can sell your firearms privately to another individual. Again, the purchaser’s PAL will have to be verified through the CFP and possibly CFO, depending on the class of firearm. Your local gun shop may also handle purchases, consignments, and estates. If you don’t have one nearby, here are two resources to consider.

Switzer’s Auction & Appraisal deals with estates daily. They provide 24-hour service and can quickly pick up firearms and related paraphernalia across Ontario. For a fee, Switzer’s will transport everything to its location and sell it at its next bimonthly auction. It sells on consignment and receives a commission.

Paul Switzer views this process as advantageous because, “If it is sold through auction, it’s settled in a timely way — not one gun at a time like the gun shops.” With 500,000 hits and 2,000 bidders on average per sale, he says, “The fair market value is immediately determined through the auction process.”

Ellwood Epps provides a similar service. While its customer focus is on collectors, hunters, and target shooters, it also handles several estates a week and has considerable experience exporting firearms. Both companies offer these services outside of Ontario.

According to Winkel, Ellwood Epps prefers to purchase firearms and all related materials outright, so the estate is settled quickly. Its website is updated several times daily as Elwood Epps relies on quick turnaround on sales.

Considering a donation

If you’re considering donating your firearms to a museum, it’s best to contact them first.

As Kim Reid, curator at the Peterborough Museum and Archives, points out, “The museum must consider historical value, relevance to the community, and the museum’s collection policy, condition, and size of the collection.” Increasingly, community museums are referring such requests to institutions like regimental museums or the National War Museum.

For the gun owner

Show your spouse where you keep your guns, keys, PAL, and any applicable registration certificate. Also, talk with your family about your wishes and receive theirs. Consult with experienced professionals and consider your dispersal options. Draft your firearms estate plan, then review your draft plan with the CFO and finalize it. Share the plan with your lawyer to accompany your will. Be sure to reread your will every three years and pass on your guns when you’re ready.

For the spouse

Know where to locate your partner’s PAL, keys, inventory, firearms, ammunition, and registration certificates (if applicable). Next, enlist your spouse to review their firearms estate plan and will with you. Afterwards, encourage the executor to take possession of said firearms. Oversee the firearms’ valuations (in inventory) so you can be an informed seller. Engage a gun shop or auctioneer to collect and sell the remaining firearms and paraphernalia. Then deposit any revenues with the estate.

Canadian Firearms Program

The Canadian Firearms Program is led by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The CFP website is your “go-to” resource for firearms legislation. The “Fact Sheets” section is especially helpful.

Chief Firearms Office

Your provincial Chief Firearms Office (CFO) is a key resource that can help with advice and direction, both during the planning and the actual dispersal of the estate’s firearms. Chief Firearms Officer Dwight Peer encourages firearms owners to consider a plan as a preventative measure. He cautions that, “When there is a significant collection with restricted and prohibited firearms and there is no plan, it becomes a significant transfer issue.” On weekdays, two CFO staff are dedicated to phone inquiries and concerns. They can be reached at 1-800-731-4000 ext 7503.

Estate lawyer

A formal will is an integral part of your firearms estate plan because you can’t control your demise. Sébastien Desmarais, a tax and estate lawyer with Pryor Tax Law in Ottawa, cautions that, “One size does not fit all.” Choose a lawyer who has experience dealing with firearms in estates. His article, “Estates and Firearms: A Tricky Asset to Handle”, provides a good overview.

Executor

Choosing an executor(s) is a key consideration. Desmarais recommends having either one or three executors to avoid deadlocks — ideally at least one with a PAL and privileges appropriate to the firearms. He encourages executors to read the Firearms Act and regulations, as well as the CFP’s “Storing, Transporting, and Displaying” fact sheet.

If your executor doesn’t have a PAL, don’t be alarmed. An executor generally has the same rights as the deceased had to possess the firearms. The executor is responsible for notifying the CFO of the client’s death by filling out RCMP form 6016 “Declaration to Act on Behalf of an Estate.”

In addition, they will need to provide the CFO with a copy of either the death certificate, letters of probate, or a document on official letterhead from a coroner or police service. As long as the executor has possession of the firearms, the registrations (for restricted and prohibited firearms) should remain in their care. Once the firearms are transferred out of the estate, the executor can send the deceased’s PAL and registrations to the RCMP.

Transferring to police

If the executor or spouse wishes to have the firearms transferred to the police while the estate is being settled, they should request “protective custody.” Unless it is your wish, they should not turn the firearms over as a “quit claim,” as that authorizes police to dismantle and destroy them. In either case, the executor should contact the police to arrange for the transfer rather than showing up unannounced at the station with firearms.

Pulling it all together

After you’ve completed your firearms inventory, consulted with experts, considered your options, and discussed dispersal with loved ones, write down your intentions. You now have a firearms estate plan. While the plan doesn’t replace your will, it does inform it. Your will is a legal document that identifies what happens to your estate after you die. It should reflect your wishes as outlined in your dispersal plan. The will should also address power of attorney. This gives someone else the authority to make decisions for you if you’re incapacitated.

Without a will, disposal of your firearms gets more complicated and takes longer. With both a firearms estate plan and a will in place, you’re as prepared as possible to pass on your firearms in a safe, compliant, and fairly simple manner. It’s your gift to loved ones during a trying time.

Originally published in Ontario OUT of DOORS magazine’s 2019-2020 Hunting Annual.

I thought I had this covered off extremely well but had not considered “asking the people to whom I am bequeathing” my firearms at all – just assumed they would want them!

It is a good call to check with them!

Thank you,

Peter