Ontario anglers and hunters need to know about deer ticks and the chronic problems they can pass on.

Over the last two years, Robert Ralston has seen good days and bad. When he’s feeling well, he goes out for brief walks, enjoys the fresh air and his rural surroundings, and dreams of when he will be able to hunt, trap, fish, and work in the outdoors again. When he’s feeling poorly, which is more often, he endures chronic joint and muscle pain and barely possesses enough energy to hold a conversation or get out of bed. Robert Ralston is a victim of Lyme disease.

The 47-year-old Parry Sound-area resident has been suffering from its debilitating effects since September of 2007, after being bitten by a tick while working in the bush near his home.

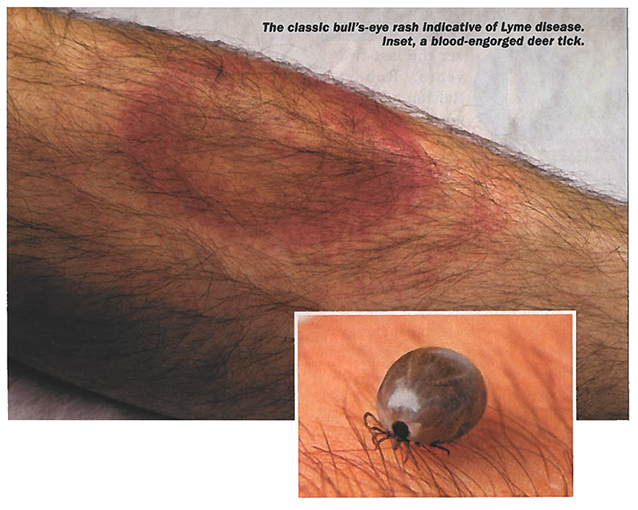

“I had just cut down a pine tree and I felt a needle-like pain” he explained. ”At first, I just assumed that a branch had poked me. But later, I noticed a bull’s-eye rash around that area.”

Bed-ridden in two weeks

Flu-like symptoms followed quickly, and within two weeks Ralston was bedridden – so sick, in fact, he had to cancel his annual moose hunt. His symptoms included joint and intra-muscular pain, as well as an incapacitating fatigue that lasted 14 to 15 hours at a time.

His family doctor, upon hearing about the symptoms and the classic bull’s-eye rash, quickly diagnosed his illness as Lyme disease. Unfortunately, a blood test returned negative and the diagnosis was dismissed.

“I was floored by the result,” Ralston said. “So, I went online to find out more about this disease and was shocked to learn I had 60 of 76 known symptoms.”

Even so, he says, his doctor didn’t give this any credence. Instead, he put his faith in the test results and, because of this, convinced Ralston he simply had a cold. Yet, by mid-October, Ralston was still suffering. By Christmas, his health had deteriorated further.

“I phoned my doctor around that time and said, ‘I need help. This is killing me.”

Over the holidays, Ralston was determined to learn more about his suspected condition, and, through the Ontario Lyme Disease Association, found a doctor specializing in its treatment. About that time, he also recalled similar rashes he endured 4 years prior, while logging in the Sarnia area – rashes that were thought to be caused by ringworm or poison oak.

Fortunately, the nurse at his doctor’s office had also done a bit of research during that period, says Ralston. As a result, in the new year he was referred to a Toronto-area doctor who specialized in Lyme disease.

Not long after, a clinical diagnosis was made and later Ralston tested positive for some Lyme-disease-related coinfections. Now, though still sick, he’s finally receiving the treatment he needs to get back on his feet.

The great imitator

Jim Wilson, President and Founder of the Canadian Lyme Disease Foundation (CLDF), says Ralston’s experience isn’t unique among Canadians who have contracted the disease.

“It’s frequently misdiagnosed in Canada,” said Wilson. “Sufferers are told they have chronic-fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia. Sometimes it’s mistaken for arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, Lou Gerhig’s disease, lupus, and even Alzheimer’s. It’s called the Great Imitator for a reason.”

Wilson asserts that Canadian doctors have a poor track record in detecting Lyme disease, partly because they’ve been told it’s uncommon and partly because of the method of testing. Canada, he says, follows U.S. Centre for Disease Control (CDC) surveillance criteria, which are flawed.

The problem, according to the CLDF Web site, is that many of those who sat on the panel when the CDC criteria were set were in “various levels of conflict of interest, including vaccine patent holders, other Lyme-related-product patent holders, medical-insurance consultants, etc.”

The CLDF and many scientists around the world disagree with this testing procedure, says Wilson. The CLDF, in fact, claims it consistently misses 50% of Lyme-disease cases. He believes proof of the failure of current testing methods is evidenced in the reported statistics in Ontario.

The Public Health Agency of Ontario (PHAO) claims that from 2005 to 2009 there were 254 reported cases in the province, with approximately one-third of them contracted by people while travelling outside of the province.

“We do not feel these numbers are accurate,” said Wilson. “It simply doesn’t add up, especially when you consider that neighbouring states like Minnesota report nearly 1,100 cases per year. We think this is due, in part, to misdiagnosis because of our testing. The worst part is that these kinds of numbers keep our doctors off-guard. In many cases, they just don’t consider Lyme disease as a possibility.”

In 2006, the federal government confirmed fewer than 50 new cases across Canada, according to Wilson. “Meanwhile;’ he said, “our foundation confirmed more than 2,000. Most, however, were diagnosed by fully accredited labs outside of the country, where testing differs”

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) concedes that the current testing procedure might return negative in patients with Lyme disease in the early stages or in those who have received antibiotic treatment, but notes the accuracy of the test improves as the infection progresses. This is why it now recommends a clinical diagnosis first, based on the patient’s symptoms and the risk of exposure to infected ticks. Blood tests, they suggest, should be run in conjunction with the clinical diagnosis to determine the presence of antibodies to the bacteria.

The cause

If there’s disagreement regarding the prevalence of the disease, there’s none regarding its transmission. In Ontario and most of eastern North America, the black-legged tick (Ixodes Scapularis), more commonly known as the deer tick, is the primary vector.

Initially, the corkscrew-shaped Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium that causes Lyme disease is carried in mice, squirrels, birds, and other small animals. When ticks in their larval, nymphal, or adult stages feed on these infected carriers, they pick up the bacterium and then sometimes pass it on to the next human they attach to.

Ticks typically wait in ambush on low-lying vegetation, generally no more than 18 inches off the ground, or in woodpiles or rotting logs. Their bite often goes unnoticed at first, since they inoculate the area, for all intents and purposes freezing it.

Not all ticks carry Lyme disease, even in areas where it’s prevalent. Nor does a bite from an infected tick always result in the disease, especially if the tick is removed in the first 24 hours.

Current science supports the notion that the disease can’t be passed from person to person, either. And, although it’s contracted from the bite of a deer tick, the PHAC reports that you can’t get the ailment from eating venison. Interestingly, deer seem to be immune to it, as well. Dogs and cats, on the other hand, do get it, but can’t pass it to humans.

The effect

Borrelia burgdorferi, once in your system, can cause a variety of problems. The PHAC says generally within two weeks, but as early as three days from the bite, flu-like syIJ1ptoms such as fatigue, chills, fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, and swollen lymph nodes are experienced.

If untreated, the disease progresses to the second stage, which can last up to several months. Symptoms in this stage include central and peripheral nervous-system disorders, multiple skin rashes, arthritis and arthritic symptoms, heart palpitations, extreme fatigue, and general weakness.

If proper medical care isn’t received, the infection progresses to the third stage, which is difficult to treat and can last from months to years. This nightmarish stage has several serious symptoms, including chronic arthritis and serious neurological problems. If contracted during pregnancy, adverse effects on the fetus, including stillbirth, can occur.

As horrible as Lyme disease is, death is rarely a direct outcome. Having said this, Wilson says suicide is sometimes a result of misdiagnosis, inadequate treatment, or the poor quality of life that chronic sufferers live with.

Who is at risk?

If you live in or visit areas where deer ticks are found, you could potentially contract Lyme disease. In the early 1990s, in Canada, deer ticks on Long Point on Lake Erie’s north shore were the only ones identified as having an endemic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Now, additional high-risk areas have been identified in isolated pockets along Lake Erie and in the vicinity of the Thousand Islands National Park on Lake Ontario in the eastern part of the province.

This is not to say Lyme disease is restricted to these areas. Infected ticks often hitch rides on ground-oriented birds such as robins, so the disease can potentially show up almost anywhere a bird flies to.

The risk is far greater for hunters, anglers, and others who work or play in the bush, particularly in those areas where the disease is endemic. Children, because of the time they spend outside, are also susceptible. Dogs and cats are at risk, too (typically the disease’s onset shows with arthritic symptoms and lethargy).

Spring and fall are the most common seasons to contract the disease. This coincides with the breeding cycles of ticks and peak activity times for hunters and anglers. The PHAC says most cases are reported in June and July. These are often from bites acquired in May. October and November are also periods of increased human-tick interaction.

Prevention

Avoiding the disease in the first place is best. With this in mind, Wilson says awareness is your first line of defense. “If you know that Lyme disease exists, you will know what you need to do to minimize your risks,” he said.

Simple things, such as sitting on a deadfall, picking up firewood, or walking through low brush could mean exposure to Lyme-carrying ticks, he says. “These are typical haunts for ticks,” he said. “It’s where they lie in wait for their next blood meal.”

This is not to insinuate you should shy away from these areas. Instead, it merely indicates increased, but easily achieved precautions, are in order.

This means wearing long pants tucked into your boots or socks, long-sleeved shirts or a bug jacket, and using a good insect repellant that contains high concentrations of DEET. Choosing to wear closed shoes, rather than sandals, is also prudent. Many Lyme researchers also prefer light-coloured clothes, so ticks that attach can be seen more easily against them.

Even with all these precautions, ticks can make their way to bare skin. This is why John Scott, a research consultant for the Lyme Disease Association of Ontario, said, “If you’ve spent time in places where ticks might be, it’s a good idea to take a couple of minutes each night to check for them. Strip down; use a mirror or get your spouse to examine areas you can’t see or reach. If you find and immediately remove ticks, you reduce the risk.”

When it comes to pets, the PHAC recommends a good flea and tick collar and regular inspections.

Immediate action

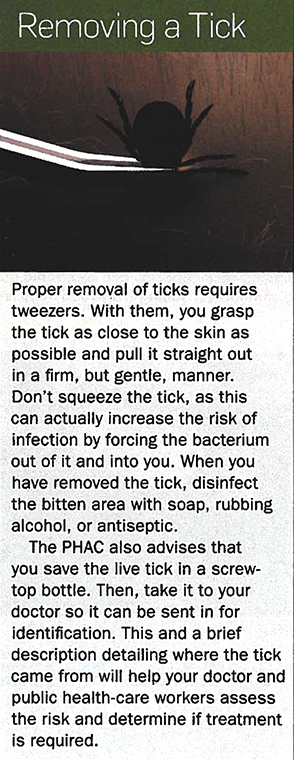

If prevention is the most important thing, the action taken when you find a tick attached to you or anyone else comes in at a very close second. As previously mentioned, prompt removal is crucial. Transmission of the bacterium is unlikely to occur if the tick was attached for less than a day or so, says the PHAC.

If you didn’t notice the tick right away, but do notice a bull’s-eye rash (which only happens approximately 30% of the time) or feel any of the early symptoms, especially a flu that occurs outside of the normal flu season, you should see your doctor and voice your concerns.

The main thing to remember is, when diagnosed early, Lyme disease is much easier to treat. Generally, a two-to four-week course of antibiotics will cure the disease, if diagnosed in time. If, however, it’s only recognized in its latter stages, treatment can be more complex and the disease can definitely be harder to treat successfully.

The future

Lyme is now considered an emerging disease in Canada. The PHAC believes it will be far more widespread across southern Ontario in the next decade, a potential result of climate change and increased distribution via songbirds heading north in spring. As such, and partly because of the urging of organizations like the CLDF and the Ontario Lyme Disease Association, this illness is beginning to receive the recognition it once lacked in this province and country.

There are still plenty of questions to answer. For instance, Wilson says a significant percentage of the 1.5 million Canadians that have diseases like multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, ALS, lupus, and the like might have actually been misdiagnosed and are instead suffering from advanced stages of Lyme disease.

“We need to determine what the true prevalence is,” said Wilson. “That will help direct government policy and appropriate funding.”

In the meantime, “There’s no reason to stop enjoying the outdoors,” he said. “But, there’s certainly good reason to educate yourself on Lyme disease. It’s here to stay.”

Originally published in the August 2009 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS magazine.

Leave A Comment