Take it from these survivors, you don’t want to be dealing with this affliction.

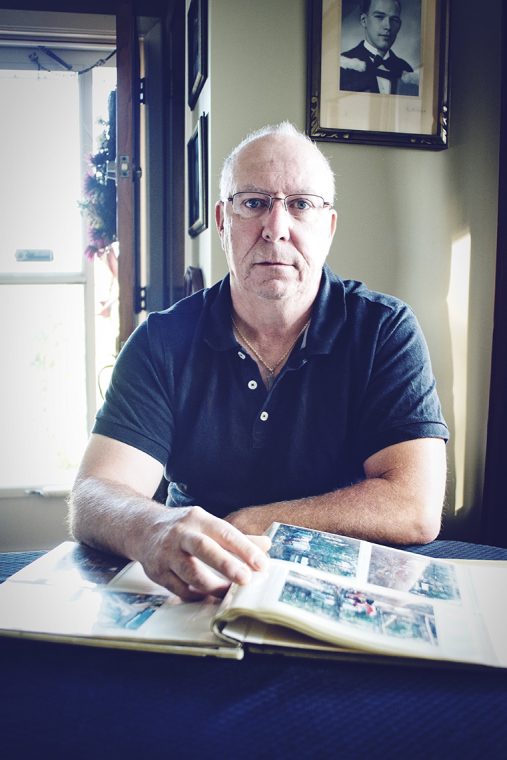

Walter Brown has a pretty good idea how and where he contracted Lyme disease.

He was having a decent hunt in November of 2015, staying at the camp he belongs to near Havelock, north of Highway 7. It’s an area he has hunted for years. He had been looking forward to the season and in the days leading up to the hunt, his anticipation had grown even greater. The school custodian would be off work for a week, out with good friends, and the forecast called for balmy weather.

Looking back, he thinks it’s the weather that changed that hunt from a highlight of his year to the cause of a terrible health scare. “I remember it. If anything it was too hot. That’s how I think I got it. It was hot, so we were wearing T-shirts. I took my jacket off, put it on the ground, then I put it back on. That’s probably where I got the tick.”

The 58-year-old who lives just outside Peterborough wasn’t completely unaware of the threat of black-legged ticks, also known as deer ticks. “I’d read a little bit about it… not a whole lot. But I have hunting pants with draw strings at the bottom that I can draw tight around my boots.”

On the Thursday of the hunt, he came back to the camp and headed for the shower. That’s when he noticed what appeared to be a rash under his arm. “It looked like a bull’s eye so I got looking closer in the mirror. I just saw the red target and when I leaned in I thought I saw the tick.”

He shared his discovery with his hunting mates and figured he’d better head to the hospital in Peterborough, a little under an hour away. There, he says, they removed the tick and told him to take it to Peterborough Public Health (PPH) for testing. Brown felt symptom-free, he recalls, but he did as the doctor suggested. He also decided to end his hunting trip early.

Delayed onset

It was January before it would cross his mind again.

“I really didn’t think it would be a problem. It didn’t bother me until I started having symptoms… a loss of balance, blurred vision. I noticed at work that my balance wasn’t great.”

Brown talked to his wife and they wondered if his symptoms were tick-related. He had yet to hear back from the health unit so he got in touch with his doctor. They discussed the situation, and he says he was advised to wait for the test results, which finally came in near the end of February. They were positive for Lyme disease. He started treatment immediately, but by then his symptoms had worsened.

“I was starting to have sweats and severe stomach aches. I had a lot of heartburn, back pain, joint pain… as soon as they put me on medication I was better with some of it.” The stomach and back pains abated but the dizziness and vision problems persisted. He also began to experience severe arthritic pain. “For two months I hobbled around here,” he said, gesturing to his living room and the kitchen beyond. “I could barely walk. It hurt to walk. My hands were swollen.”

And, he says, he felt alone. He didn’t know anyone else dealing with the disease so he had no one to talk to who could relate to his concerns. To make things worse, his symptoms weren’t just physical.

“It attacks your central nervous system, and your brain. You get anxiety and depression.”

By late summer 2016, Brown says he was coping better. He was still on medication but he was back to work half days after nearly five months of sick leave.

Brown still suffers some arthritic pain, but is looking forward to joining the hunt again. “It’s not going to keep me away from that. No way.”

Spread the word

Brown has made sure his hunting buddies are aware of his experience with the disease and he plans to do his part to make them, and other hunters, vigilant when it comes to preventing it.

Recently, the province stepped up its efforts to educate Ontarians about Lyme disease. Just months before Brown was bitten, Haldimand-Norfolk MPP Toby Barrett saw his infectious diseases bill (Bill 27) pass with unanimous support. It called on the government to establish guidelines for the prevention of vector-borne diseases through education and research. And in July 2016, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care released its Lyme disease action plan, which includes a 10-step education and awareness strategy (www.ontario.ca/lyme).

The plan has four pillars: access, connect, inform, and protect. It details the need to improve the availability of information and the necessity to provide tools and support for people in need, and it calls for a strengthening of intergovernmental coordination of Lyme disease initiatives and prevention. Among its goals is to develop an Ontario Lyme disease research agenda.

Once the action plan is in place, it will require buy-in on a national level.

Health unit help

A number of health units in Ontario have initiated programs to get the word out at the community level. Under the title “Tick Talk,” PPH published a paper in 2016, advising residents on what to do if they find a tick on their body. Among its recommendations, it suggests people include the following information with their tick:

• The name and date of birth of the person to whom the tick was attached;

• Location on the body where the tick was found;

• Approximate length of time the tick was attached;

• Where the tick was acquired, along with recent travel history;

• Record of any symptoms; and

• Healthcare provider’s name and city of practice.

Wanda Tonus, public health inspector for PPH — the health unit where Brown took his tick for analysis — says a tick is first sent to a public health lab for identification.

“There are a number of different species of ticks and the one responsible for Lyme disease in our area is the black-legged tick or deer tick.” She estimates it can take up to 10 days to hear back on identification, depending on the time of year and how busy the labs are.

If it isn’t a black-legged tick, no further testing is done. If it is, it’s sent to the National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg. Determining whether the tick is positive for the bacteria that causes Lyme disease can take up to two months, Tonus says.

PPH advises those bitten by a black-legged tick to seek medical attention even if a positive diagnosis has yet to be returned.

“We recommend that people let their physician know they have submitted a tick. They are best to follow up again if they are experiencing any symptoms,” Tonus says.

Tonus says the health unit keeps a running tally on the number of ticks sent for testing.

With a few weeks left in 2016, she put the figure at about 71 for the year. Of those, none had tested positive for the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. That contrasts with 2015 — the year in which Brown was bitten — when 36 ticks were brought in to the health unit and three tested positive.

Tonus suggested greater public awareness may have contributed to the increase in testing in 2016.

No age limit

Wes McCoy, now 18, had his own run-in with a black-legged tick in June of 2016, near Tobermory. He wasn’t sure what it meant when he first noticed it.

“I was on the last day of my camping and hiking trip with my school. I had just woken up and was preparing some breakfast for myself and I noticed that my ankle was very itchy,” said McCoy, who lives in Orangeville with his parents and younger brother.

He went in for a closer inspection. “When I looked down at my ankle I noticed the red ring and a little black dot hanging off it. I know for a fact that it was not there 10 minutes before, when I put my sandals on after getting out of my tent.” He instinctively pulled it from his leg. “I knew it was a tick right away but at the time I did not know to keep it so it could be tested and I threw it away. When I got home that night I told my mom about it and she sent my dad and I to the hospital to get it looked at.”

McCoy did not feel sick; he just had an itchy ankle. McCoy was given a single dose of antibiotics by the doctor at the hospital. However, after following up with his family physician, he was put on a month’s worth of antibiotics to battle any potential problems. The drugs made him so ill and weak he was reluctant to take them, although he did.

Today, McCoy says he is symptom-free, but he’s careful to take precautions whenever he’s in the woods. “Now I know to wear socks with sandals while camping,” he says with a laugh.

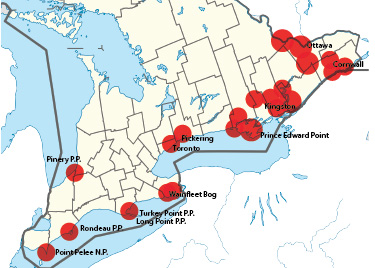

Black-legged tick locations

Black-legged ticks can be found almost anywhere in the province. Here are some high-risk areas documented by Health Canada.

Try interviewing some chronic lyme patients ,you make it look like life gets back to normal .I haven’t meant anyone with the chronic condition that has their life back yet , i’m still waiting after 19 yrs.The disease makes you sick, the people you have to deal with during that time , take your life.

My neighbour has the disease. He battled with it and the medical system here in Thunder Bay for almost two years. Finally, as a last ditch approach his family took him to the U.S. where he was tested and quickly diagnosed with the condition. Now he still has to travel for his treatment, as he has had no luck with Dr.’s here in On.

What a shame There is a “go-fund- me” account set-up to help with there medical and travel costs.

This is a travesty that our medical system has to re-invent the wheel instead of taking direction from nearby areas that have been battling this for years.

For anyone venturing outdoors it behooves you to check out No-Fly-Zone clothing sold by Mark’s Work Wearhouse. It’s one of the best defenses against these little b*******s! The clothing is impregnated with permethrin which is a miticide and actually kills ticks. Do your research. Simply slapping on some DEET and tucking your pants into your socks is completely inadequate protection.

According to the manufacturer, the permethrin is effective through 70 washings which they believe is about the life of a garment. For years, in Canada, the government would not allow Mark’s to advertise No-Fly-Zone clothing as being effective against Black legged ticks, but they finally relented and allowed it, providing the permethrin-treated clothing had a non-permethrin liner, which, from everything I’ve read, is totally unnecessary. I think there was a couple of other provisos. Nonetheless, it doesn’t affect the effectiveness of the clothing. Another brand of permethrin-treated clothing is Insect Shield which is available through Amazon (I just checked). There are other articles of treated clothing through Insect Shield, such as socks, that Mark’s don’t, or didn’t carry.There may be others – my research is out of date.

Some communities in Ontario have Lyme patient support groups. If you are, or suspect you are, a victim, it would serve you well to check them out.

For more information, check out canlyme.com.