People are seldom vague about their opinion about the table qualities of waterfowl. Those who love it may not always provide the best reference. Folks who think they don’t like it are apt to remain entrenched in this strong belief, based no a limited sample of poorly handled or cooked birds.

People who qualify their taste preferences with conditions about how scrupulously the birds were cleaned and cared for, talk about marinades, cooking methods, and enhancements, like sauces and wine selection, are probably among the fowl’s best table references. These folks have tried waterfowl in several different ways and keep an eye out for constant improvements. Careful attention in the early stages is not wasted on the birds as the multi-step transition from marsh to the table will have an influence on the quality of the meat and palatability of birds.

Waterfowl species

Notwithstanding proper methods of preparation and cooking, most hunters are aware that each species of waterfowl, and often the same species taken in different locations, seem to have an innate influence on the table qualities of the birds. In an extreme example, a carefully plucked and cleaned, fully fattened adult male common merganser will definitely provide a different taste experience from a similar drake mallard. Within this spectrum of taste fall all the other species, each with a certain, innate table quality, which is the point of departure for the cooking experience.

While we all harbour personal preferences for ducks on our table, there is no guarantee that a mallard, black duck, or even a woodie will meet quality expectations. Waterfowl are migratory birds and often travel vast distances to arrive in Ontario. They bring a wide variety of flavours that reflect the characteristics of where they’ve been. Hunters experience a local “slice” of that contribution to the taste and palatability spectrum, influenced by bird care, cooking method, and other factors.

Taste, tenderness, and palatability

There are a few common denominators in preparation and cooking lore for waterfowl. The first among these is the general observation that fat birds are a better proposition for roasted fowl than skinny birds. For many species, the fat layer under the skin is a delightful taste experience, very different from breast or leg muscle tissue. However, the subcutaneous layer of fat can sometimes harbour adverse flavours that may not be detectable to others. My wife, Carmen, cannot eat birds roasted with the skin on, while she very much enjoys stuffed duck breasts wrapped with bacon and put on the barbecue.

For those who do enjoy roasted birds, these are usually much better when they carry an adequate fat supply covering most of the body. Even the noble canvasback falls short of the culinary leg-end that birds arrive skinny after a long migratory journey. So if roasting is your intention, pick early season migrants, like blue-winged teal, woodies, or wigeon, that may be fully fattened in the first couple of weeks of the season. Once migration is in full swing for species like ring-necks, scaup, canvasbacks, mallards, and green-winged teal, (along with less abundant species like gadwall, pintails and others), however, you will find semi-to fully-fattened birds are ideal for the roaster and a delight to eat.

It’s all about age

Age is the single biggest factor in determining the tenderness of waterfowl, which has a huge bearing on the selection of cooking methods, and how well the table experience unfolds. Unfortunately, aging waterfowl is not something most hunters know much about, and it becomes more difficult to do using plumage as a guide as the season goes on.

Young ducks and geese in early fall are moulting into their first basic body plumage, so they look a little ragged compared to adult birds. Young Canadas are smaller than adults, have more indistinct off-white cheek patches, and may have juvenile tail feathers that are split and worn. Many of these changes in plumage characteristics also occur in ducks. An important clue for identifying young of the year ducks and geese is that the skin may rip if they are plucked aggressively.

As fall progresses, young birds continue moulting into adult plumage, making it progressively more difficult to rely upon plumage characteristics to distinguish young from adult birds.

Waterfowl by the tail

One of the best early season indicators of age in waterfowl is the presence of worn tail feathers, which are often faded and frazzled. Juvenile tail feathers usually have broken tips that appear as notches. Several species will carry at least one or more notched tail feathers until mid season. By contrast, tail feathers in adult birds are much larger, appear in solid shades of slate, brown and/or white, and have well-defined, sturdy tips.

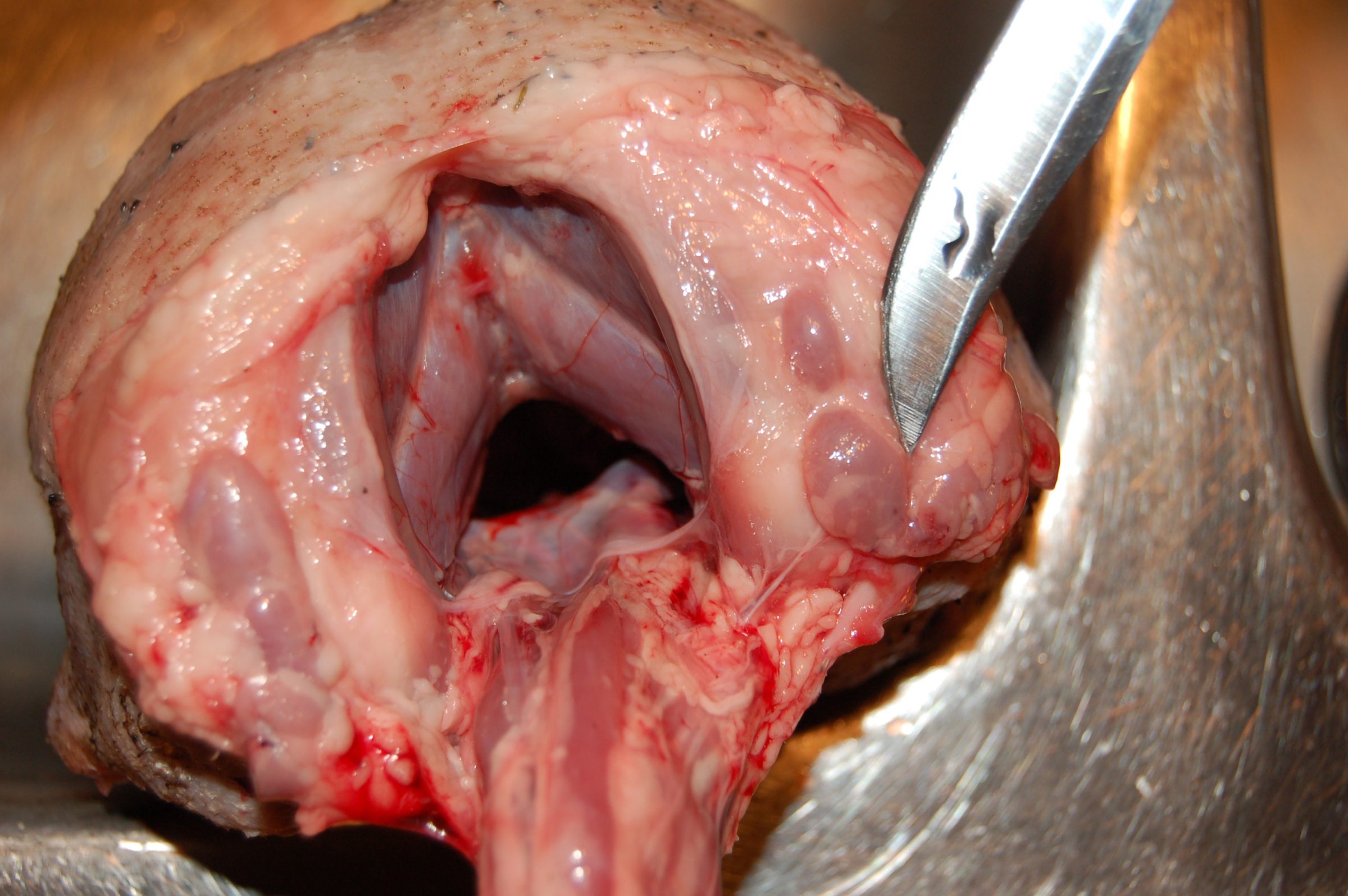

Look at the thymus

As fall progresses, the first alternate, or adult plumage is acquired, making it difficult to distinguish young of the year waterfowl from adults, using plumage characteristics alone. While conducting physiological studies on post-breeding redheads in Manitoba, I noticed that the thymus gland (located in the neck or thoracic region) remained highly distinguishable throughout the fall in young of the year redheads, but also in other species of immature ducks and geese.

The easily visible size and presence of thymus lobes provide hunters with a useful method to distinguish young of the year birds apart from the general adult population. Since geese are much larger than ducks, the thymus gland with its numerous lobes is an easily distinguished indicator of bird age. I always check for the presence of the thymus by cutting open the neck before deciding to cut or pluck a bird.

These four birds I harvested show the plumage changes in drake wood ducks in the fall as they move from juvenile, left, to adult plumage.

Diet and the environment

The diet of a bird is the most obvious link for waterfowlers to the culinary experience, yet it is also one of the most deceptive. Corn-fed mallards, with layers of yellow fat, seldom fall short of expectations on the table, even if the same birds continue to gorge on zebra mussels back at the roost site. To the observant waterfowler, the skin of fat plucked mallards comes in several hues, from a deep butter yellow to pink and various shades of white. Plucked fall-fattened bluebills, meanwhile, often range in shades of rose to stark white.

Where these birds have been feeding on large freshwater fairy shrimp, other invertebrates, seeds, and pondweeds, they tend to be good to excellent table fare, but not in all cases. I have found that the skin colour of fat, plucked birds is not in itself much of a predictor of the table qualities of the bird. A fat Ontario mallard is most often a great table bird, but so is a mallard taken in any of the three prairie-provinces or points east to New Brunswick. The same generalization is much less reliable for fall-fattened scaup and several other species.

Hunters are quick to link flavours and the dining experience to the relative amounts of plant or animal life ingested by the birds. Generally if a species tends to eat plants, many feel that these birds are better eating than those consuming more animal matter. This is not always the case. Redheads, with their love of a musky algae called “chara” are a difficult taste challenge wherever the two overlap. Our delicious Ontario ring-necks are virtually inedible unless skinned, if taken in the marl lakes and pothole country of Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

More diet considerations

Gadwall, wigeon, and many other species may have strong flavours where they occur on lakes and marshes in salt flats on the prairies, where at least part of their diet may be algae. The environment used by the birds needs to be considered with diet in formulating any opinion on the palatability of waterfowl. Birds arriving in southern Ontario from Manitoba and Saskatchewan may also be carrying strong flavours in their skin fat reserves from their places of origin.

Ontario is blessed with many species of waterfowl that stop here en route to their wintering areas. These species occupy several different feeding niches and they can adapt readily to new food types and feeding opportunities. Most of these changes help the birds restore energy reserves depleted in migration, and may allow them to replace fat reserves harbouring unpleasant flavours, after a short stay in Ontario.

However, local circumstances, like food abundance and distribution, water chemistry, and a myriad of other factors, may influence the palatability of whole, skin-on, roasted waterfowl. In most cases, these issues can be overcome by skinning the birds and marinating the meat for a day or so before fast-cooking with high heat, or on the barbecue.

An overview

The first decision in dressing birds for the table is whether to pluck or cut it (removing the breast and leg meat). Body condition, like whether the bird is fat or skinny, or the extent of damage done by shot need to be considered. Whether you pluck or cut will determine the best method of cooking and the overall culinary experience.

I always check for the presence of the thymus by cutting open the neck before deciding to cut or pluck a bird. This photo illustrates the presence of the thymus gland in a young of the year Canada goose, taken on October 23.

A note on geese

Canada geese and snows can be notoriously tough and sometimes fraught with unpleasant flavours early in the season. While young birds among our resident giants are great for roasting or meat dishes early in the season, Canadas arriving from the boreal forest and points north can be skinny after this first, long leg of their journey, and may carry some untoward flavours from their grazing in the north. Young snow geese are readily determined by their grey feathering and once on agricultural lands for a week or so, these birds are transformed into delightful table fare.

To hang, or not to hang meat

It is hard to ruin good birds. They take a lot of handling abuse (and often neglect) and still come out of the oven, or off the grill better than “not bad.” The flip side is that it is also easy to make good birds great!

One of the most controversial issues in preparing game and waterfowl in particular, is the question of whether or not to hang birds, and if so, for how long. Hanging waterfowl to tenderize the meat and improve the flavour is a firmly held European tradition. In roughly six decades of cleaning and cooking waterfowl, I have tried on many occasions to hang birds for various lengths of time and temperature. The largest benefit to hanging birds in my experience, is to tenderize the meat. While a certain level of tenderizing can occur with hung birds, I would recommend choosing young birds for the roaster and cutting adults and suspected adults for different meat dishes.

If you choose to hang birds, I would suggest cleaning them completely first. This allows the air to access all edible parts of the bird from the inside out. The “hanging” process can also be done in a number of days in the fridge, keeping any potential problems with air circulation and temperature at bay.

Make haste when cleaning

Sometimes bird processing doesn’t get done when it should, particularly in the warm weather of the early season. Decomposition proceeds quickly, especially evidenced by a growing patch of green-stained skin around the vent of the bird. This greening of the vent and abdomen is accelerated when digestive tissues like the small and large intestine are loaded with food or fecal material and have been pierced by shot. Some hunters may overreact, looking to dispense with the birds because of spreading green in warm temperatures.

I make it a point to clean these birds as soon as possible and cut away the green tissue. For those hunters familiar with the “hanging” process, some green tissues on whole, un-plucked birds is not cause for alarm, or reason to discard birds. Given that a bird starts to decompose the moment it is killed, and is eventually recycled through natural processes, every successful hunter must consider how long to accord the process of decomposition, before cleaning and cooking a bird.

Hanging birds is a personal choice and one that is often made much easier when the consumer of such delights has a well-defined sense of smell and taste. I have neither after seven decades on the planet. The point being that many people detect tastes and smells in waterfowl that are simply unknown to others. This variance in the ability of individuals to smell and taste prepared or cooked birds, contributes significantly to opposing views on the benefits and values of hanging waterfowl and other game.

Bob’s best

OOD’s Bob Bailey has been waterfowling in Ontario for 60 years. He’s a has eaten pretty much everything legally huntable. Here are his favourites, in order:

Top Ontario favourites. These birds, fully fattened, are the best:

- Wigeon

- Teal

- Mallard

- Ring-necks

- Wood duck

Bob’s worst

My least favourite Ontario table candidates include common merganser, red-breasted merganser, long-tailed duck, and the three species of scoters. To turn scoters into a culinary delight, take the skin off the breast meat and marinate at least overnight. BBQ the stuffed (various filling options), bacon-wrapped breasts until medium-rare. Stuffed scoter breasts can have the consistence and flavour of the best meat to have ever graced your BBQ. Be sure not to overcook, and eat it while hot!

Originally published in the 2021-2022 Ontario OUT of DOORS Hunting Annual.

Dr. Bob Bailey began his career as a waterfowl biologist with the Canadian Wildlife Service before becoming an advocate for conservation and the future of hunting, fishing, and trapping. Bob has written for OOD for over 30 years.

Reach Bob at: [email protected]

Leave A Comment