The noisy, tandem spinnerbait kicked up a mini-wake as it churned through the pin weeds fronting the marshy lower end of Lake Simcoe’s Cook Bay. Occasionally, it would ride up and over a stalk, that had been crushed or wind-blown into a horizontal position. Then it would plop back into the water under the aquatic jungle.

Surprisingly, it’s big, single hook seldom caught on stringy reeds. There was nothing subtle about the fish’s attack on the absurd looking chartreuse creation. We saw its wake coming before the gurgling lure disappeared in an alarmingly large boil, followed by a surface leap that shook the pin weeds for yards around.

Into the weeds

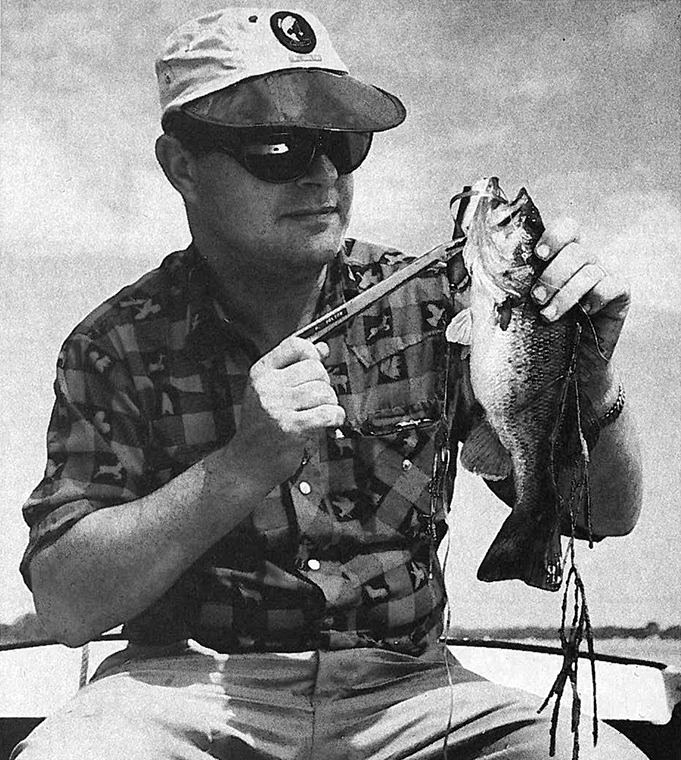

Peter Brewster, my fishing companion, lost no time with formalities. He raised his short baitcasting rod overhead and physically forced the thrashing largemouth bass into open water, where he soon had a firm grip on its lower lip. No trophy by many means, the stocky, olive-green, four pounder was still a respectable catch. It was one of the better examples of a dozen or so bass that we had connected with that morning on Cook Bay. The catch even included one smallmouth. All had been taken from a variety of cover having one thing in common; they were what most anglers refer to as “weeds” and religiously avoid.

If you’re interested in largemouth bass, but hate fishing “weeds”, then you had better abandon the sport. The two go hand-in-hand. And that part of the largemouth’s abode is not the place for flimsy ultra-light tackle. Too many opportunities exist in its stump and stickup world for a bass to make good an escape by wrapping a line around wood or weeds and snapping it like sewing thread. And if you think adorning the jaws of escaped bass with hardware is sporting, your sense of fair play certainly differs from mine, and your wallet’s a lot thicker. Common gear used by bassin’ fanatics is usually spooled with lines testing 12 to 20-pound breaking strength, with 12 or 14-pound-test a good, all-round choice.

Bait getting better

The largemouth bass, more than any other fish, is probably responsible for not only keeping the art of baitcasting alive, but forcing manufacturers to refine and improve the equipment. Baitcasting tackle has always been capable of pin-point accuracy in the hands of an accomplished caster, but it has now been refined so that even a mediocre fisherman can hit a bull’s-eye consistently. And if you’re a stump and spinach angler, accuracy in placing a lure or bait in a 10-inch circle means the difference between “fish on” or arm exercise washing baits. The days of knuckle-busting casting reels are long gone. Today’s baitcasting reels are superb examples of modern technology. Depending on the manufacturer and model, they come fitted with sophisticated drag systems and at least one of several types of anti-backlash devices. While that bug-a-boo of the baitcaster, the backlash or “professional over-run”, still hasn’t been completely solved, many of today’s baitcasting reels make it darn hard to “bird’s nest” your line. You can get by with spinning tackle, but accuracy suffers.

As for suggestions on rod actions, I’ll include some generalities as we proceed. However, the range of baitcasting tackle is so broad that I feel a final, up-to-date choice is best made with the help of top store’s sales staff.

The largemouth bass is typically a creature of “structure”. In southern Ontario, most anglers have come to recognize the largemouth as favouring relatively shallow water, closely aligned with heavy cover in the form of aquatic plants, fallen timber or standing stumps.

Following the food

Unsuitable water temperatures or oxygen levels will force them out of cover to seek favourable conditions, but these occurrences are rare in Ontario and usually brief. And even then they seldom travel farther than is necessary for their comfort or food seeking needs. In many U.S. impoundments, largemouths do spend more time in deeper water and over other structure, such as rocky shoals, dropoffs and sunken road beds. But movements of their main forage fish – the threadfin and gizzard shad – dictate these variations as much as other factors, such as water temperatures and oxygen content. The bass simply must follow the food. In Ontario, we have few such parallels. Largemouth fishing here, for the most part, will be in relatively shallow, obstruction-filled waters.

Bucketmouths, as they’re fondly called by anyone who has glanced at their oversized routes-to-no-return, are really not that hard to catch, once you find them. And there’s no better place to start than right in the heart of the aquatic jungles that they live in. There they find shade, cover and food.

Knowing the flora

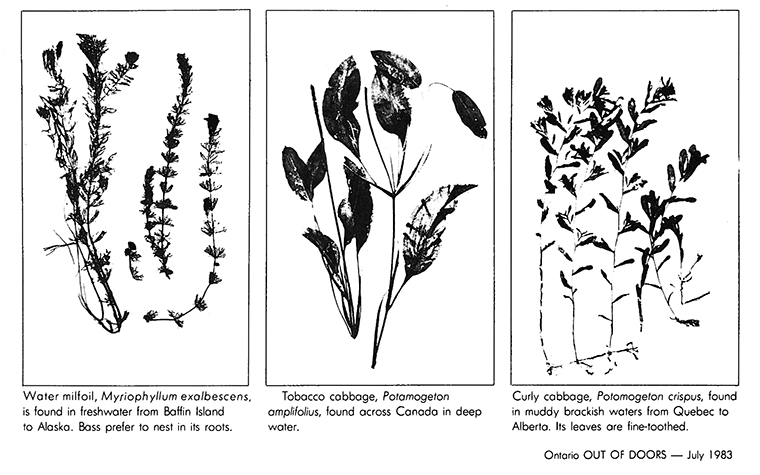

Aquatic plant growth in a typical largemouth lake follows certain patterns according to depth, water clarity, and type of bottom. Shorelines are often lined with cattails or rushes, while arrowheads may be anchored around the perimeters. Large or small expanses of lily pads often mat the surface at irregular intervals.

Many varieties of feather “junkweeds” take over from there. As one goes deeper, expanses of elodea, sand-grass milfoil and then coontail become more prominent. Coontail is easily recognized by its resemblance to the after appendage of its namesake.

At the deeper edges of weedgrowth, you’ll start seeing the “cabbage plants”, or, as many anglers call them, “muskie weeds”. There are two main types – the tobacco cabbage and curly cabbage. In some lakes, stands of pin weeds or wild rice can be found in the shallows.

The pattern varies only slightly. For example, there are many great boggy largemouth lakes where rushes and reeds are undercut, with wave action constantly setting floating islands of these thick mats adrift to lodge in other weed-growth areas. Sunken timber and trees, even rock piles, are also features of many good bass waters that have been flooded, and, for our purpose, must be considered part of the largemouth’s total environment.

As you can see, the largemouth’s territory actually covers quite a depth range, right from the shoreline out to the 20-foot depth or more.

Depths will differ

The actual depths will differ for the different succession of weed growth. In clear lakes, sunlight penetrates deeper, allowing plant growth to occur at greater depths. Off-coloured bass waters limit light penetration and the depth to which significant plant life can maintain itself.

This versatility of greenery allows the largemouth to find both food and shelter at different depths. And each presents different challenges for lure or bait presentation by the angler.

Many lures for bass are very versatile and can be used throughout their territory. Others lend themselves best to certain applications.

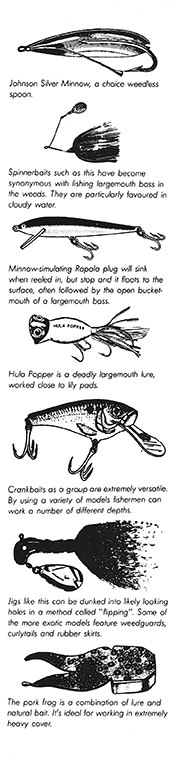

Basically, largemouth lures fall into the following categories: plastic worms, twister tails and minnow bodies for jigs and spinners, leadhead jigs, spoons, spinners, spinnerbaits and buzzbaits, topwater, floating plugs, and floating- diving plugs.

In heavy weed growth, a bait that doesn’t gather vegetation is a must. Plastic worms, rigged “Texas-style”, are one such lure. They can be used with a bullet slip-sinker to reach down in openings in the weeds or for fishing along the edges of growth, or weightless for dragging topside through the thickest of greenery.

Special hooks, with offset shanks, are made for fishing plastic worms. For weedless rigging, the point is pushed into the top end of the worm, threaded through for about three-quarters of an inch, and then brought out again before burying it back in the worm until it is almost ready to break through again. When a bass hits a plastic worm, you have to set the hook hard to bring the barb through the worm and into a fish’s mouth. A rod with a sensitive tip is needed to cast and detect hits, yet for proper hook setting it must have a medium-stiff butt. There are a host of rods available just for the purpose, usually in the five-six-foot range, and they’re generally suitable for using lures as well.

Combos are effective

Bass often take a worm as it sinks. So a combination of retrieve-sink is often effective. However, what works on one day doesn’t always the next. Experiment constantly with lure retrieves until you hit a winning combination. There are so many styles of plastic worms on the market – all effective – that choosing a selection can get costly. Starting with some of the “action tails” is your best bet. The six inch size is a good average, but it’s best to have some from four to 10 inches as well. Some productive colours are black, purple, chartreuse, yellow, motor oil, brown and blue.

When to set the hook after a bass takes a worm is often the subject of much conversation. Too soon and you miss the fish. Too late and he’ll drop it. I play it safe when a bass hits by dropping the rod to create slack. When the line retightens, I set the hook. It’s not a failsafe method, but assures a high hook-set rate.

Next to the plastic worms rigged weedless, the single-hooked so-called weedless spoons are lures that fully live up to their reputation. They’re great for skittering across floating weeds or lily pads and dropping into pockets of open water. Pork rind tails, either plain white or frog finished, have always been traditional garnishes for these bass spoons. They’re tough and flutter enticingly. However, another good addition is a three-inch twister tail, although not as durable as rind. Some anglers pref er spoons with “living rubber” tails.

All hail the spinnerbait

One of my favourite bass lures is the spinnerbait, a combination of spinner(s) and a leadhead jig. They cast well, can be fished with the blade(s) kicking up a fuss on the surface or below it, and their single hook, protected by the spinner’s shaft, is surprisingly weedless, although still prone to grabbing the odd bit of greenery.

The buzzbait is also in the same category. However, it is more suitable for fast retrieves just on the surface. These lures often turn on bass, when all else fails. They have one or two large propeller spinners on the shaft, ahead of a flat jig.

A word about spinnerbaits, buzzbaits and bass lures in general, with regard to water clarity. Many lures send out no vibration or sound. You must depend on bass seeing them to get a hit. In dirty water, the majority of lures are useless. That’s where the spinner-buzzbaits, and I should include full-bodied lures with a rattle in them -are extra versatile. They send out vibrations that bass can hear and home in on, even if they can’t see them.

Bass hug structure

While on the subject of water clarity, remember that bass are not going to be wandering ail over looking for food in. stained or cloudy water. They’ll stay close to some structure, letting food come to them. They may be near a stump, a weed clump or a rock. To catch bass in these conditions, you must cast right on target. In other words, cast practically in front of the fish, so that at least it has a chance of hearing the lure, even if it can’t see it. Pick definite structure to cast to when the water is cloudy and use “noisy” lures.

You can jazz up your spinnerbaits by adding a twister tail to compliment the usual rubber skirting they come with.

Just about any ordinary spinner, such as the Mepps or Vibrax, which manufacturers claim also sends out vibrations, will also catch bass. But you’re restricted to fishing them above the weeds or in other open waters, unless you use a model with a “weedless” treble hook. Such weedless trebles have a fibre or wire weed guard and do deflect vegetation to some degree. But, all too often, they are also the cause of missed fish. Using such a hook is really a compromise in weedy waters. You need it to fish, but expect your hook-up rate to fish to drop accordingly.

Try different approaches

I wish largemouths would feed exclusively on the surface. Nothing beats watching a big bucketmouth blast a top-water plug. However, they seem to limit their surface feeding activity to certain periods. Calm mornings and evenings are tops, with daytime action unpredictable. About the only thiing you can do is try surface lures when conditions seem right -dead calm. Some long-time favourites are the Hula Popper, Jitterbug, Dying Flutter; Heddon Torpedo, Crazy Crawler, Zara Spook and Bass-Oreno. Most of the baitcasting and spinning models have either a broad face or propeller blades to create a noisy surface attraction. They’re among the most fascinating lures to fish with. Generally, they are allowed to sit for a while after being cast to bass hideouts. Then a reel-rest-reel again retrieve is used. Most bass hit fairly soon after the first movement of the bait. However, I’ve seen times when the only way you could interest bass was to race a surface lure back to the boat at top speed. So don’t be afraid to try different approaches.

More versatile than the true topwater plugs are a host of lures for bass that float at rest but dive when retrieved. They range from the original Rapala to the new crankbaits. How deep they dive depends on the size of the lure’s lip and the speed of retrieve. Some will only dig down a few feet, while others, with larger lips, can be “cranked” down to 15 or more feet in a relatively short space.

For largemouth, the crankbaits, as many of these floating-divers are called, offer an extremely versatile line-up. By having some of the shallow and deep divers in your tackle box, you can cover a wide range of depths, from just ticking the tops of sunken weeds, to running the edge of a deep-water weedbed. And floating crankbaits can also be used with a twitch and rest retrieve as surf ace lures.

When all else fails

One technique that often triggers strikes from indifferent fish is to actually rip crankbaits through the weeds. Why bass still find greenery adorned lures worthy of attacking is open to conjecture, but do try the method when all else fails.

And never be afraid to bump bottom regularly with crankbaits. Stir up the mud. Bass will think it’s a feeding baitfish or crayfish.

I particularly like shallow-running crankbaits when casting to specific structure, such as stumps or standing sunken timber where weed growth isn’t too heavy. Always fish the shady side of such structure, if the sun is casting definite shadows. That’s where bass will be. Choose a selection of finishes in crankbaits. Good starters would be perch, frog, shad, shiner, crayfish and chartreuse.

Leadhead jigs may seem an illogical choice for fishing shallow, weedy bass waters, but that’s far from the case. Combined with a technique called “flippin”, leadheads are quite useful for probing pockets in the weeds. And some of the flat planer or slider styles can be skipped and skimmed over all kinds of obstructions.

Flippin’ for bass

Flippin’ is really nothing more than dropping a jig or other lure into small openings in vegetation where an actual retrieve style of fishing would be out of the question. A quiet approach with the boat is paramount to success for the technique, and it works best in stained water, where fish are less spooky. Enough line is hauled off the reel so that a manageable length hangs from the rod tip, more in the left hand (or right, for you lefties). The jig or lure is then swung or flipped into the small pocket or beside other cover. If there’s a bass in residence, it usually lets you know right away by belting the bait as it sinks on the first cast.

At most, make a few vertical lifts with the lure, or twitch it, before lifting out and recasting, unless water clarity is low, in which case give fish a longer time to find the bait. The most popular flippin’ lure is a leadhead jig with a “living rubber” skirt, and often a twister tail body for added action. I prefer a style which also has a small spinner incorporated into and under the body of the jig. Flippin’ rods are slightly longer than conventional baitcasting models, since the extra reach is an advantage. They have a medium-soft tip, but a beefy butt, needed to haul bass out of a salad patch before he burrows into the mess for good.

Perhaps the time-tested pork chunk “frog” belongs properly in the live bait category, but I consider it a true lure. With its chunky, frog-shaped body and fluttering split-tail, imitating legs, the action one gives in the water is very lifelike. Rigged with a large, single weedless hook, you can chuck a chunk just about anywhere with impunity. They’re basically· almost a surface lure, ideal for skittering around stumps or lily pads – just the places a bucketmouth would expect a frog to appear. I like to use them without any weight, so casting distance isn’t always as good as with heavier lures. But that’s seldom a handicap.

By now, you should be getting a pretty good picture that ye olde spinach patch isn’t really all that formidable. The tools an angler needs to catch bass there are extensive, namely the lures, rods and reels we’ve briefly covered, and the where-to is becoming clearer.

Two outfits are ideal

Let’s go on a typical bucketmouth bash, based on what we’ve learned so far. To be really versatile, we would have two or more rod-and-reel outfits set up in the boat. One may be rigged weedless with a plastic worm, for the thick stuff, another with a spinnerbait. Just having a quick choice of lures ready for different situations lets you really cover the waterfront. An opportunity to make a quick cast to different structure may be lost if you have to take the time to change lures. If you’ve wondered why shots you’ve seen of bass anglers on the pro tours have boats bristling with rods, now you know. But in general, two outfits will serve our purpose.

A hazy sun is just an etching on the horizon, as you cut the motor and start poling or drifting into the shallow bay that you know largemouths inhabit. Of course, if you’ve invested in an electric motor, you’ll be listening to its quiet hum, as it slithers the boat toward a patch of lily pads you’ve spotted tucked over along one fog-shrouded shoreline.

Selecting your favourite surface plug, you position the boat so that you can cast across the front of the pads and the entire retrieve will be mere inches from the platter-shaped discs. All goes well and the lure lands with a plunk on the far edge of the cover. Letting the disturbance settle, you resist retrieving immediately. When you do start, it’s just a gentle twitch, before letting the lure rest again. You’ve made a wise choice. A bucketmouth barges out from beneath the floating pads and inhales the inert lure with an unnerving gulp. It had probably heard the lure splash down immediately, and its curiosity had it nervously watching from its lair. When the lure didn’t move, its confidence built up, but its innate caution prevented an immediate take.

But the wait was enough to convince the bass it was a small bird that had fallen into the water, or a mouse or a frog.

The pad beds yield several other bass for your efforts with surface lures, but as the sun lifts above the horizon and strengthens, a breeze riffles the water, putting an end to ideal topside conditions.

But a switch to a spinnerbait proves that bass are still active under the pads, extending the action there a bit longer. In all probability, you’ll stay with the spinnerbait for most of your bassing in the shallows, since it’s such a versatile lure.

Searching for shade

The sun is up now, starting to noticeably cook the back of your neck. The bass also feel the sun, and shallow water action seems to have gone dead. But has it? A cast to the shady side of a sunken stump finds you hooked to another angry bass that had been hiding in the dark recesses of its roots. Fishing the same pattern of shady sides of cover, you find more bass around the timber.

Nearing noon, the sun is hot enough to fry an egg on your aluminum tackle box. The bass seem to have disappeared. Moving out to deeper water, you speculate that fish have done likewise, It’s still early summer, and patches of coontail haven’t yet reached the surface. As a result, it’s hard to read exactly where pockets or openings are. Spinnerbaits and shallow-running crankbaits, fished over the weeds, produce a few bass, but it’s obvious they’re really not too eager to leave cover.

Time to probe that patch with a weedless worm, feeling for those openings as your slip-sinker drops into them. The bass are there, and you enjoy several hours of continued action.

For variety, you even work the water around clumps of cabbage weeds, at the edge of the vegetation, with a deep-diving crankbait. But today there are no bass there, although several sleek pike try their darndest to chew the paint off your lure. Perhaps in a few weeks, when water temperatures go higher, those same cabbage weeds will also harbour some bucketmouths.

Back to topwater

It’s darned hot now, and time to call it quits for lunch. After a snooze in the shade, you head back out to catch some more action as bass reverse their movements back into the shallows. By the time the sun becomes a glowing fireball on the horizon, you’re again tossing top-water baits.

That’s what the typical scenario for a day’s largemouth fishing on a southern Ontario lake could be. Variety. Experimentation. And usually enough bass to keep things lively. The jungle they live in isn’t hard to explore. It just takes the proper tools.

So there you have it. Those seemingly horrid places where largemouths lurk are really not that formidable. And the action they provide is well worth becoming a “Popeye of the spinach patch”.

Originally published in the July 1983 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS magazine, and authored by former editor-in-chief John Kerr.

Leave A Comment