Gail Olivier knows the importance of good public relations. A trapper for more than 25 years, she knows what some people think about her occupation. “A lot of people don’t understand trapping and why it’s done,” said Olivier, who also runs a hunting and fishing lodge. “During the winter, I invite guests from the lodge to come with me when I check my beaver traps. We make a day of it. We cook hot dogs, drink hot chocolate, and examine the traps. This way, they see firsthand just how humanely the trapping is done. It gives them a truer picture of life in the bush country, and trapping.”

Gail Olivier: Trapper and Lakeland Lodge operator

Olivier tends a 100-mile-long trapline near Sudbury, Ontario, in addition to a remote line north of the district. Her Lakeland Lodge on Lake Wanapetei, which she operates with her husband and four kids, sits in the middle of one of the traplines. The lodge hosts hunters and anglers year-round, in addition to the trapping activities.

She takes good care of her trapping area, managing it much like a farmer, cultivating the land and farming things such as poplar and cattails to enhance the region for the animals. “I plan a whole strategy for taking the animals, so I don’t trap too many one year and hurt the next season,” she said. “I have more animals today than when I started. At one time, I could only take six beaver. Now, I’m allowed 100.

Her father kindled her love for the outdoors by taking his young daughter into the bush country on his gold-prospecting and hunting expeditions. On those trips, Gail shot birds with a .22, a present on her ninth birthday. Snares for rabbits soon followed.

“Most of the kids I knew wouldn’t go with me into the bush,” she recalled. “They were afraid, so most of the time I went alone.”

Going solo

Even today, she doesn’t mind doing it solo, except for the companionship of her dogs. Most times, her husband, Bucky, doesn’t accompany her because he teaches at a local university. “It doesn’t bother me to be out there alone. I love it,” she said. “I never thought of the bush as something to be afraid of. You don’t fight it, you go with the flow. My mother-in-law once said, ‘The bush doesn’t just get into your blood, it gets into your soul.’ I believe that.”

When she met Bucky, it was love at first sight. She was visiting his younger sister, and he came in wearing his hunting clothes and a knife hanging from his belt. “He showed off a bear he had just gotten, and I knew he was the one for me,” she said, laughing.

One of the first things they did together was buy a remote trapline. It was so far out, no one else wanted it, except the young, starry-eyed couple.

“I thought it was perfect,” she said. “It was something we could manage as we saw fit, without much outside intrusion.

A great family life

When kids came along — she has three of her own and a foster son — they travelled with her. As infants, she carried them on her back, papoose-style.” They stayed warm in

bunting blankets,” she said. “As they grew older, they learned what they could and couldn’t do in the wilderness. Sometimes, they brought friends along. Their friends still keep in touch with me.

“I guess some kids would have thought I was a strange mother, but to my kids I was normal,” she said. “They thought all moms were like me. For us it was a great family life.”

Occasionally, her kids still go with her. “My son, Bucky, is a very humane trapper and is conscious about what he does in the bush. My other son, Paul, likes to guide, and my foster son, Brian, helps out a lot at the lodge. (Meanwhile) my daughter also likes the bush country. She doesn’t trap, but she understands it and helps me. She also goes to the trapping conventions, and understands the need to harvest the fur.”

Understanding trapping

Understanding trapping is part of Olivier’s public-relations goal.

“I don’t trap to kill or catch animals,” she said. “I try to get people to understand the whole picture better, and how to work with nature and not against it.”

Besides increased beaver quotas, due to good management, Olivier’s take on other animals has gone up.

Her present quota is 89 marten rather than the original six. She also can take more than a dozen mink, but is fearful of over-harvesting the area.

“I try to trap a cross-section of my line for all my animals, so I don’t deplete any one spot,” she said.

Timber wolves as quarry

Timber wolves can be a problem in northern Ontario, but they’re also part of Olivier’s quarry. She has several mounted wolf heads, along with other game, at her Lakeland Lodge.

“The wolves are the cleverest of animals. They seem to know when I’m in the woods, just as my dogs know they’re out there,” she said. “The wolves tear up the game trails to let me know they’re aware of my presence. I’ve also had them circle my tent, howling and growling.” She just waits until they go away.

Contrary to beliefs, Olivier feels wolves don’t kill just when they’re hungry.

“I’ve seen wolves take down a healthy cow or bull moose in deep snow. They tear it apart, scattering the bones all over, and then go out hunting again.”

None of these dangers seem to deter her from setting wolf traps in both snowy and clear weather. “I come back and check the snares for wolves every 24 hours. If I don’t, the other wolves will tear the trapped one to shreds,” she said. “There have been times when I’ve come back to just a lot of fur.”

Snares and stretching

She uses snares almost exclusively along her lines. “I don’t use leg-holds too often because you have to get back to them within 24 hours, and I can’t always do that with the miles of traplines that I have,” she said. “If snares are set properly, they are very humane. If an animal does manage to back out, that’s okay because I’ll get it the next time. I plan to be here awhile.”

During the trapping season, Olivier sometimes sees her husband only on weekends. He’s an experienced trapper and hunter, but he’s also a professor of chemistry at Laurentian University in Sudbury. When not in class, he comes up to his wife’s trapping area and packs out the skins. She does all her own skinning and stretching. The furs go to auction or she sells the tanned skins at the lodge.

Olivier’s dogs usually travel with her in the bush. Summer visitors to Lakeland Lodge are greeted by these friendly animals. “I sometimes call them the dirty dozen,” she said. “I let guests know about the dogs. They don’t bother anyone, and it’s nice having them around.”

Besides the dogs, other animals call the lodge island home. There’s a moose named Bullwinkle, Gomer the raccoon, and owl named Boo, and Sweetheart the bear cub. Olivier adopted the moose and cub after their mothers died. Both will return to the wild when nature calls.

Screening guests

Olivier’s trapping and hunting attitudes lap over a great deal into her life as a lodge operator. She screens all potential guests, whether it’s for a fishing or hunting trip. “Our main lodge, as well as the cabins, have skins and heads on the walls, and I don’t want anyone being put off by that and complaining about ‘all the dead animals’.”

Lakeland Lodge is about an hour from the Sudbury district. The rustic but warm housekeeping cabins are on a 12-acre island, which is accessible by float plane or boat. Those coming in by car can park at a beach facility, about a mile across from the lodge. If guests don’t bring their own boats, they can hoist the chartreuse signal flag, and within a few minutes someone at the lodge will pick them up in a boat. Night-time arrivals signal with flashlights.

Black bear management

Black-bear hunts are a big part of Olivier’s business during the spring and fall seasons. She or her family bait traps for the bears, and hunters wait in tree stands far off the main roads. Just as she lays down strict rules for herself when trapping, she keeps an eye on her hunters, too.

“People ask me what’s my hunters-to-bears-ratio. I really don’t have an answer for that,” she said. “I ask hunters to shoot bears that are more than 175 pounds. (Also,) I tell them to count to 100 before shooting to be sure. What’s the sport in taking a baby bear that weighs less than 75 pounds after it’s dressed? I think the day of shooting the 40- to 50-pound bear is gone.

“In the fall, I also tell our guests to watch for the sows,” she said. “Most have young cubs following behind. If you shoot the mother so close to hibernation time, the 5- to 6-month old cubs usually don’t survive. That’s probably what happened to the mother of the cub I have. The cubs are our future.”

Olivier says the hunt itself should be reward enough. “Going into the bush just to shoot any size bear isn’t a challenge,” she said. “You have to have the patience. The big ones are out there. Obviously, I can’t stop our hunters from shooting small bears, but I’m not sure I’d let them come back again.”

Her methods must work because most guests return or are referred to the lodge. for those lucky enough to shoot a trophy bear, Olivier or a family member will skin it, pack the meat for travelling, and include cooking recipes.

Good fishin,’ too

Besides the hunting, fishing for smallmouth bass, walleye, pike, yellow perch, and lake trout is good on Lake Wanapetei.

“It’s a good life here,” Olivier said. “And a lot of it is public relations. Sometimes I wish some of the big antis and those people from the big cities would come here and see just what really goes on, especially with the trapping. We live off the land, and we love it.”

The anti-fur lobby

The Fur Institute of Canada‘s Executive Director, David Gladden, said few people in Ontario, perhaps 40 to 50, are actively involved in anti-fur activities in southern Ontario. But he said they make a lot of noise, especially in the media, creating a “skewed perception” of how widespread the anti-fur movement really is. He said there are no documented cases of serious harassment of people wearing furs, although several furrier shops have been spray painted and had their locks glued or otherwise vandalized. Toronto police say they have no way of knowing how widespread such activity is. Gladden said activists stopped harassing fur-wearing women in the street after a few years back after the institute stressed they were only adding to violence and harassment against women. The fur industry’s biggest enemy right now, he said, is the recession.

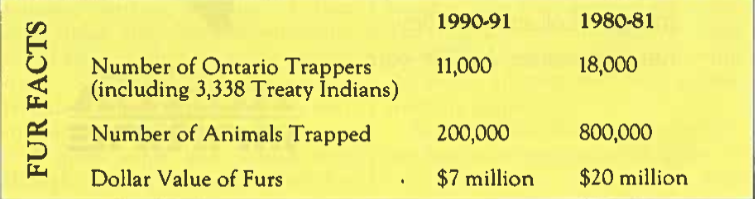

What’s trapped

According to Dr. Milan Novak, MNR’s Fur-Bearing Animal Specialist, the most commonly trapped animals in Ontario are muskrat, beaver, martin, fisher, fox, and raccoon. Muskrat are the most commonly trapped, but martin and beaver account for the highest dollar value. Enormous fluctuations in the demand for furs dates back to the 1600s, and while the fur business has always been cyclical, the cycles cannot be predicted, he said.

The dramatic drop in trapping has had no effect on some species, he said, but for animals such as the beaver, more problems are encountered in the way of flooded roads, pastures, and woodlots, as well as chewed trees on cottage properties.

While there are no hard figures, an increase in rabies can be at least partly attributed to fewer foxes being trapped, he said.

Originally published in the February 1992 issue of Ontario OUT of DOORS

Please check the most recent Ontario hunting and fishing regulations summaries, as rules and regulations can change

Click here for more outdoors news

Good for you, trapping is wildlife management if done with intelligence and love for the outdoors

I run TB147, and share the same attitude.